Friday 29 June 2012

A Note on English football values

We joke a good deal about England, but England v Sweden was one of the most exciting games of the tournament. By the end England had scored 5 goals in 3 games which is not bad. Goals let in 3. England lost on penalties in the quarter final. This isn't incompetence, it isn't doom, it's something of a pleasant surprise all things considered.

I make glib jokes about the team, millions of us do, then I get bored by the glib jokes and feel somewhat sick of my own. Each national culture produces its own brand of excitement and the team that represents it is bound to reflect it some degree.

The key values for English national teams have not been guile, grace, art, strategy - they have been courage, heart, commitment and solidity. The fiercest criticisms have been directed at what is perceived as lack of these. That's what we get. We don't like ego so we don't get genius. We don't like apparent lack of effort so we don't get variety of pace.

Individual players and managers alter the balance this way or that but the centre of gravity is what it is. English sports values are essentially military values. Most English sport is trench warfare.

Thursday 28 June 2012

Worlds 2012 Memoir, Fiction & Truth (6)

Alvin Pang

I have Alvin Pang's provocation in hard copy so will quote from it. Alvin is from Singapore. He started with a funeral and ended with ashes, in other words he was framed in mortality and our ways of dealing with it. This is how he began.

Just over a week before arriving here, my mother-in-law passed away. Traditional Chinese funerals in Singapore can be long-drawn affairs – we spend days camped out at the foot of the apartment block where she lived, wearing stark white and black, with token mourning patches on our sleeves – colour-coded to indicate our precise place in the family hierarchy. We stand, or sit, or kneel, or bow as the Taoist priest indicates, circling and circling the coffin as he chants on in a language and idiom incomprehensible to most Singaporeans today – since Chinese dialects were discouraged in the 1980s, we have largely lost touch with our family tongues and traditions. So the rites have become public ritual performances of mourning that leave little room for private grief. We fold paper currency meant to be burned as offerings, mix up protocols, confuse taboos, make do, wonder if calligraphed talismans we cannot read can still protect us.

He continued:

One of my very early poems describes my grandfather’s funeral, which I experienced as a child. In it, I described the same sense of dislocation, the ritual exposure of a deeply private affair, his remains stacked alongside row upon row of anonymous others in the columbarium, gazed upon by passing strangers who do not speak of him. It and other poems from that early period attracted immediate recrimination from my family -- the cultural taboo about voicing the private in public is still strong. (To this day, I don’t show any of my writing to my family: they’ve become the external manifestation of my inner critic. Truth may cry out to be heard, and readers may want the dirt, but readers don’t have to live with my relatives afterwards).

This then broadened out to the role of the state:

This question of responsibility about what is to be said and not to be said, also has a political dimension. A writer from and in Southeast Asia carries a complex filial burden: on the one hand there’s the rich imaginative possibilities available to our diverse peoples, but on the other, the pressure of having to build up a new shared sense of the canonical, of shoring up a viable dogma adequate to a post-independence, modern idea of nationhood. In Singapore, a generation of our poets have famously been admonished for “retreating” into personal lyric and abandoning the unfinished project of nation-building through public, monumentalising verse... At the same time, literature itself as a cultural tradition has been pared and pared back: in schools, in the media, in public life – it has been regarded as at worse, subversive and at best, uneconomical; a weak bet: “Poetry is a luxury we cannot afford” is the indicative quote by former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, whose memoir is tellingly titled, THE Singapore Story.

Alvin then explored the way this attitude works through the practicalities of education and publishing. He discussed these under the three headings of Infrastructure, Independence and Intimacy.

In terms of Infrastructure he considered the market and the idea of public success; in terms of independence he described the lives and backgrounds of poets, who are mostly professional people (as he is) whose sales of a thousand or two combined with state neglect encourages them to play with language; and in terms of Intimacy he talked about the use of intimate language such as Singlish (a language he himself uses in some poems). Its use means poets can write about things that are insignificant in public terms, about their own families, for instance. It allows poets to play - it almost invites them to do so,

Intimacy may not survive contact, he writes. But writing can become a means of riding the gravity of our inward and outward fascination, encircling that core of our longing. And he talks of The Burning Room, a poem where a woman spontaneously combusts after her lover departs; when he returns she is already the ash he wonders at and brushes gently away from the hood of his car. Alvin ended wheere he began, with a funeral, the description of the cremation process, saying of the dead woman:

What the ovens cannot claim, claims us. We breathe her ash-dust into our lungs, carry her home.

*

Dust and ashes, dust and ashes, wrote Browning in A Toccata of Galuppi's). We are framed by them and by ritual, the rituals of mourning a life and of running a state.

In so far as the funeral was concerned there was a form and the proprieties associated with the form. The form in Alvin's account was ancient and hierarchical: people had their functions and stations. Grief and fear, two of the key elements in death were shaped and allocated roles. Trespassing against the form was a form of sacrilege signifying a lack of respect. And this obtained across a whole range of familial relationships. The period of mourning extended beyond the primary ritual into bans against marriage in the mourning period. There were prescribed ways of behaving.

On the other hand there was the role of the state and the state education system in affirming a view of itself, presenting a face to the world. The state was concerned with the world of markets and public commercial success. The presentation of the national self was prescribed much like the ways of behaving at the funeral.

What then is the writer’s role: what kind of propriety or responsibility is incumbent on the writer, and to what degree should the writer offend against the first and reject the second? Is the writer fundamentally a solitary, the relationship between writer and reader as of one solitary to the other? If so we are not wholly part of the funeral, we resist absorption into the state. We stress the self and the truth of the self. And again if so, is that a peculiarly Western or a more universal 'we'?

A discussion of centres and peripheries was beginning to emerge. If the state, the ritual, the adult, is the centre, is the writer’s place at the edges of ritual, transgressing against its complex codes, at a point in Gail's locatable, sticky-fingered numinous childhood, far from, but aware of, the centres of power.

Syon talked about the power of stories in his culture, Iceland, where literature is the only developed form. There was some question as to how far we expect writers to speak for their cultures, their particular political situations.

But how fair is it to expect a Nigerian writer, like Chika Unigwe, a Ugandan writer, like Goretti Kyomuhendo, or, say, an unnamed Somalian writer to write directly about being of that place? How far was location actually in the local and - I think back to Gail’s point here - how far is the notion of responsibility to a place or people an obligation if one is to be considered a serious writer? Is the imagination local or metaphorical? Is it a free agent or has it responsibilities? If you are not at a centre of cultural power - say at a major Western metropolis - are you obliged, if not by moral or aesthetic conviction, to engage with that power and do what it seems to demand?

The writer's public responsibility is not just an old chestnut - it is positively ancient. Socrates is said to corrupt Athenian youth. He has a responsibility not to, says the city. Do we speak out? Do we speak on behalf of? This was a theme picked up by Chika the next morning.

Tuesday 26 June 2012

Holding post

Back late from a full day at UEA so will hold over the next part of Memoir, Fiction & Truth to tomorrow night - though I am in London all day tomorrow and might not get back till 9pm. Alvin Pang tomorrow if I can. These are all good, fascinating papers and discussions so I'm glad to be able to record them from notes and memory.

Lots of nice responses to Poetry Review from recipients and members. I have just got home at ten, now for a slice of toast and a tea, up again early tomorrow morning.

Monday 25 June 2012

Worlds 2012, Memoir, Fiction & Truth (5)

Gail Jones

Wednesday morning: Gail Jones's Provocation

Gail Jones, in her provocation, the next morning, offered us four modest proposals.We understand the irony implicit in the history of modest proposals but I don’t think her proposals were ironic. They were mostly to do with establishing a notion of self that might be capable of constructing a more generous, more complex truth. Her case was partly predicated on childhood as place, in particular the simple improvised cinema back home in her remote village where the adults sat under cover in hierarchies of race and gender but the children were in the open, fully integrated. [I was fascinated by this binary of adult / child since the adults were guilty and comfortable but their children, presumably by adult permission, were exposed and integrating.]

The four proposals were headed in bold as follows (the essential points are summarised)

1. Contradiction: This involved minority discourses, aborigine and workers’ tales, the rural outsiders. The writer works with contradictions,

2. Sticky fingertips: To write is to let fascination rule language. There is (as Bachelard believes) a poetics of space. Houses possess a mythicality, or fictive glamour, something that moves and disturbs us. Malouf uses the term ‘dense affinities’. The child leaves its sticky fingerprints all hover the place. Is writing like conjuring or building a house?

3. Trespass: The idea of the periphery being the centre. There was an aboriginal boy who sat through class carving on a crate. He was an emblem of the ‘radically local’, the trespasser from the periphery who could become the centre. Outside the Blue Streak missile was being tested on his native ground. Who trespasses on what?

4. The dark covering and the parachute: This involved seeing the body as a form of history. Georges Perec refers to the terror of parachute training. The body being cast out of the plane as a metaphor for writing.

These definitions belonged to the realm of the self, or rather to the idea of self as body and location, that could constitute a form of truth.

The word permission arose at that point and stayed with us as a wakeful companion throughout the morning. There was ‘out there’ - or perhaps ‘in here’ - a fairer, more compassionate truth, where the children in the exposed part of the rough-and-ready auditorium, might trespass onto adult territory, and the aboriginal boy drawing diagrams on his crate might enter the covered space so that we might reorientate ourselves around him. The Blue Streak missile would still be the Blue Streak missile.

[Was it possible then that Nancy’s redemption (in John’s provocation) might come by a darker route under a darker covering, as an aboriginal boy, her / his sticky fingerprints the articulations of parachuting body. Those dense affinities about which I enquired would then be bodily and locational. The space, both inner and outer, would be dense with a new idea of the self as an intimate space.]

We discussed the self as metaphor a while and talked about the way stories might unconsciously enact key childhood memories and about the way mask might be a way of approaching the kind of intimacy outlined in Gail’s presentation. Teju talked about childhood as a body, but that in reading it wasn’t physical presence that was desired but disembodiment: the mind, and writing itself, being perhaps curiously bodiless, We don’t necessarily want the writer bending over us, his or her breath hot on our necks. But it was also pointed out that children don’t expressly want to be children, that they might, on the contrary, prefer to be adults, if only because they perceive adults to be the controllers of both children’s lives and their own lives. And as Gillian noted, the lives of those in puberty are less prone to memory and interpretation.

Robin Hemley made a point about the difference between adulthood and childhood in the next session that is actually pertinent to this. He told the anecdote of the adult intruding on a children’s game of space rockets, asking if he might join in and go to the moon with them, and how the children stared back at him horrified, replying in effect: You do know we are not actually going to the moon?

[I thought that was a complex story interpretable in at least three different ways but it certainly pointed to the existence of two different worlds: the children in the exposed integrated area, the adults at the back.]

Childhood was the last time, suggested Eleanor, when we can wear a stetson and fight with a light-sabre (not her precise analogy but very close) where, in effect, we can enjoy paradox without contradiction.

*

Gail's provocation was psychologically the most complex of the five - complexity was what she herself said she desired - and seemed to me, in that sense, to deal more with poetry than with the general run of novels. If the novel is about what happens and poetry is, as Auden suggested, about a way of happening; or, to put it another way, novels are about consequences while poems are about presences, her presentation was more concerned with presences and ways of happening.

Essentially, I think, she was talking about writing as a form of social healing through a reorientation of the self. It was particularly the term dense affinities (Malouf's term, I know) that struck me. I was looking to define what the phrase meant but couldn't quite, not without metaphors. But then the cinema, the fingertips so dense with sticky affinities, the carved crate and the parachute, however real and concrete, were being invoked as metaphors. That is the condition of poetry: nothing in poetry is not metaphor.

Sunday 24 June 2012

Worlds 2012: Memoir, Fiction & Truth (4)

In the readings that evening Anna Funder gave us part of a book - Stasiland - based on research, almost a kind of legal research, in which it was very important that truth - a truth that we assume may be verified by evidence - should not be invented, followed by a passage from her new novel, All That I Am, (the book won the Miles Franklin Prize the next morning) in which characters we know to be real, Audenesque Auden for example, enter a realm in which we do not expect truth to be evidential.

Tim Parks gave us an excellent example of truth as both memoir and fiction. In his memoir, Teach Us To Sit Still (about which we had privately corresponded at the time of its publication) he rendered his experience of a meditation cure in persona himself, that self anxious, vain, comical, human, the genuine Tim Parks version of a Tim Parks who, confusingly but hilariously, merged with a parallel figure Tom Pax. In the other, The Server, (the excerpt he read is here) he invented a female figure in the same setting, inventing experiences for her that required less interiority and more observation in order, perhaps, to understand the same dramatic situation, which consisted of a specific place where specific people went to undergo specific experiences. The memoir and the fiction are parts of a triangulation of both truth and self

John Coetzee then read an absolutely gripping fully chronological story from a forthcoming novel in which step followed step as minute follows minute, to make a full ladder of minutes with countable and fully counted rungs (counted because so much depends on them). The story itself was related from a height, as observed by a member of the heavenly Stasi or one of WimWenders’s angels, who takes no particular account of story-as-character but gathers evidence, a little like Anna Funder, almost as an act of pity for humankind. For me there was something of classical tragedy in the story, an inevitability that one wants to resist as a reader, but which one recognizes as a sum of truths we have to face. It was, if you like, the opposite of the story of Nancy. Salvation was not going to be offered by the provision of a different gangplank, a smarter ladder.

Tim Parks

The three readings succeeded in questioning notions of both truth and story. Stasiland would be nothing without evidential or objective truth of the kind John might have meant in his provocation. Either someone was arrested on a particular date or they weren't. Either agent X put in a report on date Y or he didn't. These facts are legally binding. Albeit retrospectively, actual laws are being broken.

On the other hand the narrative that contains the facts might well shift into the realms of story, and in so doing shift from the unique to the typical. One might imagine a German Nancy, really followed, really arrested and interrogated, who might at the same time order these facts into a type of story.

Form, one might argue, is type. (I want to follow this up at some point later)

In Teach Us to Sit Still the evidential facts are not legally binding. This version of truthfulness requires a truth to states of mind. Its essential truths are objective reports on the subjective. We don't need to be assured that a conversation took place at the stated time in a stated place. We would prefer it to have happened verbatim, exactly as the writer relates, but even that assurance is secondary to the idea of truth as revelation of condition. The truth lies closer to the 19th century ideal as John formulated it: the character should be recognisably unique, but the truth we are directed to should be typical. Why Tim's description of his encounter with the guru seems so funny is because it performs a common level of embarrassment about the reader's own vanity. It is, what we might call, 'close to the bone' - both our bone and the writer's. In effect, the memoir is presented as a formed, perfected, anecdote of truth. The writer must know this, of course, so the skill in writing it lies in balancing evidential external truth with evidential subjective truths.

In All That I Am, we meet characters that have had real evidential lives. W H Auden might or might not have been at the places the fiction suggests but he certainly appears and speaks in the book. Proving assertions about place and time should be possible in a memoir but since we know we are dealing with fiction we understand that such criteria are essentially devices of realism-feeling, a kind of background hum to which we may refer for level not for focus.

It might however be troubling if the fictional Auden turned out to be too typical, too Audenesque, too much the received Auden. What would trouble us here is the potential duplicity of uniqueness. In fiction we understand figures to be inventions: to invent something that already has an external evidential existence seems to appropriate uniqueness. How far is Funder's Auden fiction? How far is Tim Parks's memoir Tom Pax a fiction?

Not that this is necessarily a central question about any of the books. All four books present us with a complex accumulation of forms and conventions.

J M Coetzee

John Coetzee's reading was narratively the simplest, but in many ways the most complex. Time and place were unfixed, the people, as I recall, unnamed. Certain key elements of what Barthes called informants, had been removed. The father and his young son might have been from any immigrant groups, the harbour town where they fetched up might have been anywhere that was Spanish speaking. This suggests the idea of fable, in effect an exemplary tale. See, this is how the penniless immigrant is treated.

In other respects however it was almost photo-realism. All details were concrete detail, and time - the mysterious unspecified time in which the man and his son were suddenly marooned - was counted as strictly as if a metronome were ticking in the background. The rungs of the ladder, the width of the gangplank were of the utmost importance. In the Book of Revelations, St John of Patmos gives us the precise proportions of everything in much the same way. Kafka too is precise about the terrors of the existential-diurnal. He too counts minutes in a chronological void.

Listening to the episode one couldn't help but feel the sense of haunted inevitability. I associated it less with visionary work, more with classical tragedy, where we know - and understand it matters vitally to know - that events are marching towards loss and annihilation, and that the only consolation we are allowed is our ability to count precisely and to articulate our panic into a form. That form is our consolation. Only a formal consolation, true, but where nothing else seems to be on offer, it seems to be an ennobling form.

So Nancy's redemptive story(recall John's provocation) errs not so much in attempting to find a redemptive form - we all try to find that - but in that its understanding of redemption seems too limited. It lacks the depth of tragedy or even an understanding that tragedy might exist while missing the comedy of confusions whereby the uncertainty about what mum and dad seem to have said can determine a career.

Here's an interesting formulation to play with:

exper- (trag- (comedy) - edy) - ience.

All copyright protected, trademark exclusively GS, God help his soul.

Worlds 2012 Memoir, Fiction & Truth (3)

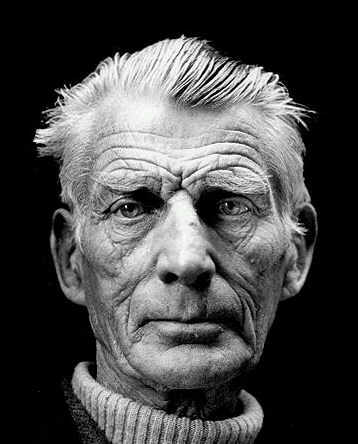

J.M. Coetzee looking faintly like Clint Eastwood

The Tuesday salon continued with the provocation by J M Coetzee (henceforth John). This took a quite different line and rather than looking to define the distinctions between fiction and memoir concentrated on what it is that makes a true life-story. Or rather what it is that might make a 'true-life story'. Or rather on what it is that might make such a story true or untrue. He recalled that the best 19th century novels offered us characters that war both unique yet typical.

He talked of a project that collected people's life stories. The title suggested six million till recently, now it talks of seven million. What were all these stories, he wondered. What makes them stories and what makes them lives?

In order to demonstrate this he gave us the story of Nancy as an example (it might have been a story he invented, it might have been one he heard). To put it very briefly, Nancy wants to go to art school and be an artist but her father insists that she do something 'sensible' and safe and she finishes up in a miserable and frustrating job. She is so depressed by this that she takes a friend's advice and goes to a recommended therapist who hears her through and finds - or suggests - that the ban on art was not her father's but her mother's. Having understood this as the truth Nancy feels a weight drop off her shoulders, goes away happy and enrols at an art school.

Where was the truth in this, John asked. Did the mother have a 'story'? Did the father? Was the point of truth to liberate Nancy and improve her life? Was her 'truth' a refutation of her mother's? Or was it a case of one relative truth, or lie, displacing another? Is what we think of as the right kind of story one in which the central figure triumphs over a personal problem?

He wondered whether objective or scientific truth might be allowed to exist. Are our life stories ours to compose? Are we the authors of our own life stories, and if we are, are we also the authors of their truth?

[Again I wondered about frames and conventions. I remembered - and mentioned - a film noir of 1948, later a TV show - Naked City, that began with the tag-line: 'There are eight million stories in the naked city'.

If Nancy's was an exemplary story of redemption (as she believed it to be) was Naked City a set of exemplary stories about crime. In other words was it not so much a matter of believing what we want to believe about ourselves as redeemable individuals, but of a location where struggles between order and disorder, good and evil, may take place? Could we then think of other such frames or locations where the 'rules' or conventions of the frame inform the nature of both story and truth. The detective's task was to solve an external crime: the therapist's to improve an inward perception of life.

Was the problem of Nancy's life, in 19th century novel terms, that it was not unique enough, that it was posited as over-typical, and hence false?

Might it be - to return to Gillian's idea of the resistant reader - that what we trust in is not the evidential truths related by the teller but the language of telling? That we trust the tellers, as we trust them, at the time?

Is trust - rather than truth - always provisional]

The discussion moved around ideas of objective truth. Some felt it existed ( i.e. gravity is an objective truth, not a story about things falling), others claimed that what we have are stories about stories that lead to objective truths. The relativisations of the postmodern mind can defer the precise position of objective truth almost indefinitely. Fortunately we did not spend much time arguing the point.

*

The evening readings by Anna Funder, Tim Parks and John Coetzee himself crystallised some of the issues so perfectly I want to write a separate post just about that. It will follow this one.

Saturday 23 June 2012

Worlds 2012: Memoir, Fiction & Truth (2)

Gillian Beer

I realise that what I present here is necessarily brief in terms of summing up of both the provocations and the conversation afterwards. I am also intensely aware it must contain a good deal of my own thoughts, but that these thoughts might have been articulated by others in different ways. The sessions begin at 9:30 with the first provocation. There is a coffee break at 11:00, which is followed by the second provocation.

Gillian Beer's provocation concentrated on the writer-reader relationship and investigated the differences between memoir and fiction. She postulated a resistant reader and reminded us that the idea of the contact between writer and reader is not automatically available.

The reader of the memoir, she said, ‘has no part in the conversation’ - what is happening is happening to a written ‘them’. The reader has to trust that what they are told really did happen as described. The distance between reader and text or author is implicit. The author may be wanting to offer us a particular reading of his or her life. We think of the celebrity memoir.

[But why should we be interested in the lives of others? Why spend time reading about others in general and one specific other in particular? There are people in whom we have some kind of interest and that may, for some, involve celebrities. On the other hand, we may feel a twinge of guilt in such 'nosiness' especially when tragedy is involved. I think of the so-called 'ghouls' at the scene of a wreck. I think of Warhol's Crash series. I think of our interest in the dead generally.

Such things are dramatic of course. But what do we seek in less tragic lives? Why are we drawn to examine them and seek the further evidences of diaries, letters and archives of scribbled notes, cards, lists? Curiosity is natural. Without curiosity there would be no human progress, no human interest, certainly no literature or any other art?

But what do we seek in memoir in particular, where the author gives a personal account of not only the events through which he or she has passed, but also the personal feelings nd thoughts associated with it? In what way is this presentation of reality as personal evidence different from other possible forms. Is autobiography different? Is the story told round a table different?]

While memoir is in some sense a 'closed' form, suggested Gillian, fiction is 'open'. The reader enters as a participant [I wanted to know more about the way the reader participates and whether memoir was quite as closed as a straight contrast sugsests], unfettered by the likelihood of things actually happening or having happened. Here we discover a different kind of belief but may also reject it by abandoning the book. Why might we do that? Is it because we don’t like the development or is it because of some factor in the narrative that we find difficult to accept? Because it betrays us in some way, breaking the trust we have placed in it?

[I kept thinking of context and convention here. Is it the proprieties of the convention that induce trust? Do we accept such conventions as the frame within which the contract between writer and reader may be established. Does loss of trust occur because the book has, in some way, broken the frame? Or could it be precisely because it has kept to comfortably in the frame, the frame being something about which we are - rightly? - sceptical. Life is not to be too easily framed. Framing, we might argue, is cliché.]

The conversation moved this way and that. Does memoir refer to an essentially locatable self? How far is that self locatable? Teju Cole questioned the standard definition of memoir. Alvin Pang wondered if memoir, given time, might become fiction. Cathy Cole talked about scepticism regarding the reality of the self. Robin Hemley quipped that the first novel was in fact often taken to be a form of memoir.

The credibility of memoir [but possibly of fiction too?] might be a matter of detail, suggested Gail Jones, a matter of detail and recapitulation. She talked of the moment of authentic feeling. Perhaps authentic feeling was what we really wanted, I added, or maybe authentication of feeling, that truth in this sense was that kind of creature. Joe Dunthorne talked of 'truthiness' - a term he thinks he read in Luke Kennard, and I first heard on R4 the other day. What was it? I said I understood it as the system whereby the listener / reader is given the impression that the speaker /writer believes so firmly in what they are saying that the listener / reader is obliged to give it some credence. (George Bush was mentioned in this context.)

On the matter of detail, it might have been Robin who told us that Marquez had written a scene where a room is filled with butterflies and, realising that this sounded merely fanciful, added yellow butterflies to make it convincing.Incidentally, Robin informed us, he taught a semester on fake memoirs at Iowa. Very popular too. There are of course a good number of examples, including some Holocaust memoirs. These books might still be good books, he added , and some of them recover critical respectability. The authentic, the true, and the facts are not necessarily the same.

Tim Parks suggested the self as a position in both life and narrative,and how hard it was to find such a narrative. He referred to Beckett's First Love and how the homeless figure demands everything and gives nothing, exactly as Beckett himself did in service of his art.

There was then the dilemma of a potentially longed for, or required misreading in poets such as Christopher Reid's Katerina Brac (the invented poet), or indeed the question of poetry as a reporter of memoir events. Christopher Reid and Jo Shapcott's Costa Prize winning books, Reid's book, A Scattering, being about the death of his wife, Lucinda; Shapcott's Of Mutability about her own grave illness. Perhaps poetry was deemed to tell us more, or give us more understanding of personal history under stress.

John Coetzee's provocation follows.

Worlds 2012, Memoir, Fiction & Truth (1)

I promised to catch up with the past week and I'm going to do so over the next few days by using the text I delivered as summing up yesterday morning. Other events may intervene or interrupt but this is the intention. The programme for the week can be found here and the earlier first blog here. What follows is a filled out version of the notes I made. Any later thoughts will be in italics and square brackets. These annual Worlds (I am tempted to say The World Series) are Writers Centre Norwich events. They do the hard hard work. The city is still celebrating being named as a UNESCO City of Literature, thanks primarily to WCN.

*

The point of such conferences is to ask questions rather than to answer them. We know there are no definitive answers to the questions asked but hope that the conversation will reveal something worth reflecting on.

In the official part of the conference, called the salon, two people provide 'provocations' or subjects which are then opened to the floor for discussion. The people round the table are writers from around the world, some very illustrious indeed. The provocations are from 15-25 minutes long. The salons are chaired by Jon Cook.

In the unofficial part, that is between the salons and the readings, people simply mix, continue conversations, get to know each other.

In the unofficial part, that is between the salons and the readings, people simply mix, continue conversations, get to know each other.

There are two essential elements to any such set of events: ideas and people. In the salon, following a provocation, the questions concerning ideas are: If so, then what? and If so, what about? In other words where does the idea lead us and what are the arguments against it? Both proposition and response tend to take the form, though not always, of If so, as in... meaning references to books and articles, as and when useful.

The people element takes the form of Speaking for myself... This is fascinating because all writers are to some degree formed by personal experience and the response to it. This is where ideas get fleshed out and become events. Now we have conviction, passion, plea and testament. The stuff of writing.

*

*

The first and most glaring question is the title of the conference, and it turns out that the original title was Memoir, Fiction and Self, which, after some thought was changed to Memoir, Fiction and Truth. This change, I suggested - and from now on the remarks constitute a subjective personal account or impression that I have tried to keep as accurate and complete as I can - indicates a certain equivalence, or at least overlap, between the terms: self and truth, a proposition that could make a conference all by itself.

The question of truth in memoir and fiction was the first theme, led by Gillian Beer and J M Coetzee. Next post for that as also for the readings.

Thursday 21 June 2012

Hard keeping up because...

...I am out early and back late for the conference every day. I'll do a summing up after - in fact I have to do the summing up tomorrow, so there will be plenty of fascinating material.

Tonight out to read in Bungay. Back late from that. But the pleasure of being on with Roger Eno, playing accordion, four lovely songs.

Now some toast and bed.

Tuesday 19 June 2012

New Writing Worlds 1

I am here for the week, starting yesterday and the programme is pretty full, including a morning salon, so it is going to be hard to keep up. There is a very illustrious list of writers, whose names will be found in the Festival Brochure. You'll find Winterson, Ondaatje, Coetzee, Parks, Shapcott, Teju Cole and the rest, just as illustrious and interesting there. Essentially, it is salons (discussion with provocations / papers by two of the writers) in the morning, then readings and events in the afternoon and evening.

It kicked off with Gillian Beer introducing Jeanette Winterson and Jo Shapcott yesterday. GB gives the fullest, most illustrated introductions ever, though some of those at the Dun Laoghaire festival in Ireland come close. The introductions were brief full enthusiastic readings of the work of both Winterson and Shapcott.

The mature, combative, surreal cartoon strip of Jo Shapcott's early poetry is justly famous. The mad cows and the Tom & Jerries are a slice of contemporary British life in full colour. The later work was understandably darkened by illness and by engagement with Rilke's poetry, but the invention remains. This time we had the Bee poems that retain the invention but are not joky, more dreamlike - a rather terrifying dream of becoming colonised by bees - and the Little Aunt poem about dementia that is shockingly moving. Shocking seems an odd choice, but it is precisely the contrast between the surreal and the tragic that seems properly so. Dementia is shocking.

Jeanette Winterson gave a muscular combative reading from Why Be Happy When You Can Be Normal, the language shifting from chatty to intense to comic, in her edgy fashion that won't quite let the reader settle. She recites sentences and reads the rest. The personal (one of the themes of the salon, in the sense of the relation between the self and the fiction) presses hard, but then shifts from the remembered to the invented.

The questions included, and then focused on the idea of learning poetry by rote (in the words of the questioner, = the bad way) and by heart (in the words of the answer = the good way). I asked what the difference was, but really I know. It's simple. It's by rote, hence bad, when taught by someone you don't like, and it's by heart, hence good, when it is taught by someone you like. Or if you decide to do it yourself.

Then dinner and back very late. It might be a little like this so hard to keep up but I'll try.

Sunday 17 June 2012

Sunday night is... Thelonious Monk

Twenty-seven and a half minutes of Thelonius Monk, Concert in Denmark, three tracks Lulu's Back in Town; Don't Blame Me; Epistrophy

That clean, just off the button sound that resists all possible invitations to appear on time and which is itself the style and the man. Let everyone else swing, I'll stumble and invent. I love Epistrophy.

*

Yesterday's Bloomsday on BBC was an absolute wonder, virtuosic, moving, its head in books, its feet firmly on the daily ground and grind. Having listened to most of it, then watched an hour of Satantango I was left exhausted but delighted. And, of course, work and reading in between.

More on that later. Today, working in the morning. Requests to use a chapter of Miklós Vajda's beautiful memoir, Picture of My Mother in an American Frame that I translated for The Hungarian Quarterly, for Best European Fiction of 2013, edited by Alexander Hemon.

Working towards a project with the poet Carol Watts, so reading through her work. And other stuff to write. As ever.

Today a suggestion from A and N that we take a walk by the sea. We have said yes too often and called off, so this time it was a yes. Drove to Winterton and walked about 90 minutes along the beach then back on the other side of the dunes, observing sanderlings, terns, one seal, and a lark, followed by a meal big enough to sink a large sea-going vessel, even though it was just the one course.

This is all very miscellaneous. I must try to be less miscellaneous.

Hungary? Don't ask.

Friday 15 June 2012

Reading / performing / spoken word: stage and page

Last night I was reading for London Liming at Rich Mix in Bethnal Green Road. Liming is described here and even more fully here, and this was our event. I think the idea was that I would bat last but because of the difficulties of getting back him at night, I actually stepped in first. Even so it was close to 2am by the time I slipped into bed.

Going on first and leaving is a matter of regret since it involves the discourtesy of not hearing your fellow readers / performers, in this case Bohdan Piasecki (you'll also find him on MySpace, and catch him in action on YouTube, for example here, where I am not the George in question) and Maria Slovakova (also here and on MySpace).

*

The venue is great, about 10 minutes walk from Liverpool Street station. I had been up at the university in the morning and went straight for the train, catching the 4:00 pm, walking over to Rich Mix just as it began to spit with rain. I didn't quite know where to go and eventually found myself in the bar watching the last 15 minutes of Italy v Croatia since, throughout the EU Championship ,the bar is broadcasting all matches live. The bar has a big screen and makes a good sized auditorium.

The customers are mostly the age of my children but then most people are by now. Before the match is quite over one of the organisers, Rochelle, finds me. I meet Bohdan and we talk (he lives in Birmingham, having completed his PhD in Literary Translation at Warwick). He's very friendly and soon we are led by Rochelle into an upstairs Green Room where we talk some more, before being taken downstairs to meet Melanie, who had invited me.

We go to the cellar for the 'salon' where there are some nine of us, now including Maria. We arrange ourselves in a circle and Chris, a poet/musician is invited to tell us about what he does. He puts on events with poets and musicians with some visuals, the music improvised, the poem already written but generally performed rather than read. I ask some questions. Then Bohdan speaks about his work and particularly translated spoken word, about the vast audiences for it in Europe. Again some questions, mostly from me. I don't speak about what I do, nor does Maria.

As this goes on I wonder what I am doing there. This is one milieu and I am of another, although the rhetoric is that we can dissolve the differences. Clearly this scene is fairly confident of itself and thrives as it thrives.

*

We return to the bar where we see Spain score their fourth goal against Ireland. The place is pretty full. Melanie comes on as soon as the football is over and announces the event. Maria does a single 'whispering' poem, just the poem, no talk, then we have a poem set against a film of footballers playing on a park. Melanie briefly introduces me. Aware that having a number of books is both heavy and clumsy I have photocopied a selection of poems I'd read from. I stand at microphone and do what I do. I can't actually see the audience and have no idea how they are reacting or whether I am doing the right thing. As a reading I am doing slightly more of a performance than I usually do, and am very much aware of timing and tone. I have a twenty minute slot 9:50-10:10 when a taxi has been ordered so I can get the 10:30 given whatever traffic or delays there may be. In the circumstances I don't know the time and though I am usually good by instinct to within about 3 minutes this is slightly disorientating. In any case, as I have already said, I don't know whether I am pleasing or boring this audience of my children's generation (as it looked before the performance began). Those coming after me are of that same generation. In the end I cut it by what, I think, is about 3 minutes short but may be as much as 7 or 8. (General principle: never outstay your welcome.) I go. Rochelle slips a £10 note into my hand for the taxi but the taxi hasn't arrived yet. She says it's a bit early and suggests it may be best to hail one. I do. It's raining quite hard. I make the train with about 10 minutes to spare so get a seat, but am worried I have done too short a gig. But frankly I wouldn't have known.

*

Clearly my age and the milieu were factors in the uncertainty I feel, an uncertainty complicated by guilt at not hearing the others (it has happened to me very often that other poets had to scoot before I came on, but in almost every case I have made it a point to listen to everyone). I did what I do well, I think, but don't know if that was the right thing to do. If I had been in the middle between Maria and Bohdan, I think (and as Bohdan too thought prior to the event) I would have had a precedent to go by, but as it was, I was in the dark, in almost every sense.

So a few thoughts or, rather, mere stubs of thought. 'Spoken word' does seem to me to overlap with some kinds of 'page poetry' a phrase Bohdan doesn't like. But am I part of this overlap? And is Bohdan right in downplaying the difference with page poetry? Spoken word seems in every way a social act. Why else speak it?

Why indeed? My poetry began with withdrawal. Being socially awkward I wrote (as I have said before) to get away from parties not to attend new ones. I needed another world, one made out of language. Language, I discovered, was my world, but that world rose out of silence, concentration and solitude, without any strong sense of the reader. For that reason it was probably too difficult, too esoteric to start with. Learning to write more clearly was partly the result of two factors: first, the sense that language was shared (how simple that sounds, but what a complicated perception in real life), and secondly, that as I gained in confidence the delight in language was, I found after all communicable.

Nevertheless, as a poet, I was born on the page, in that silent space Wallace Stevens, who has been much in my thoughts recently, so well understands. The understanding here is that some poetry, maybe most poetry, maybe the poetry I most value, is a process that is experienced by the reader in isolation. There are two pacts: the pact between poet and poem, the other between poem and reader. It is a deep and long pact, a pact not an act. The poetry isn't that which passes directly between poet and reader, but the medium in between, a medium that is transformed by the space between. The reading aloud of a poem by the poet to others is a kind of extra service; to an audience that regards itself as an audience it is different again. That milieu is somewhere between entertainment and liturgy the one passing into another. The audience is a collective. On the page the audience is not an audience. It is a mind dwelling on a concentrated space.

*

Reading is not entirely a hermetic act, but there is a kind of hush about it, in the sense that the reader's mind is entering labyrinths of its own, labyrinths that are part-palimpsest, one labyrinth laid over another. The words are just words but their layers are deeply private worlds, acts of intimacy. As intimates we can read to each other in bed, at tables, in the chairs the world has provided for us. Two or three intimates do not make a party. Not all poetry is like that, but some is. Maybe mine is.

I wondered why I had been invited. Melanie deals in both the worlds of books and in the world of spoken word / performance venues. Maybe I represented the first.

It was also an event representing Eastern Europe: Bohdan Polish, Maria Slovakian, myself Hungarian. Maybe I was the available Hungarian. But I don't speak for Hungary. Nowadays, in the poetry at least, I don't even register Hungary as a subject very much. Politically it matters to me, but the years in which Hungary was a raw discovery, when it was wanting to claw its way into the English language as English language poetry - in the years between 1983 and say 2003 - are past. I retain a faint foreign accent but I don't announce myself as a Hungarian poet. I address the question when asked.

Put it another way. My imagination has been formed by early experiences, like everyone else's no doubt, but I am not trapped in a small room with the experience. If it is the elephant in the room, I don't really want to be pointing at it all the time. I think - and hope - that my attraction as a 'Hungarian' is more publicity than essence.

Regarding the spoken word issue, I don't know in the end. I don't need to be 'down with the kids' though it seems to be mainly their gig. I have long enjoyed meeting the minds of those a different age from me, either older or younger. But do I have anything to offer them? On stage? On the page? Anywhere whatsoever?

It is not something any of us are very likely to know for sure. Best not assume.

Thursday 14 June 2012

So it goes in Hungary: the fascist at Radnoti's feast

Miklos Radnoti 1909-1944

Radnoti remembers Nyiro in his 1941 diary. I translate from the website where the news of the event appears.

Confusion about Poetry Day at Weimar. The latest article says: The Third Reich has also arranged a Poetry Day in Weimar in which invited poets from the eleven Central and European nations will take part. Hungary will be represented by the Transylvanian writer Jozsef Nyiro. Nyiro in his statement to the press said: 'We are witnessing the spiritual rebirth of Europe. I, like the rest of Hungarian literature, am happy to be able to take my part in this spiritual development. Earlier in the church I saw a beautiful painting in which Luther is pointing out the verse in the Bible that declares that we will be washed clean by blood. It is blood that will cleanse Europe. The nations of Europe are discovering each other and drawing together in the name of peace, of soul, and of spiritual revival. I support this enterprise with my heart and soul. Long live Adolf Hitler! Long live Germany! Long live the German Society of Authors!'

Now, as I copy out the article on Monday morning 3 November I am left wondering. Is it by accident I don't have a single line of his on my shelves? Not even in an anthology...'

The mayor in question is a member of Fidesz, who claim to maintain a safe distance between themselves and the perils of an openly fascist Jobbik. In effect they are 'saving' Hungary from a fate far worse.

Big deal, you say. It's just an evening and it happens to be there. Very little 'just happens' in Hungary. It is a significant gesture and there is no chance it is carelessness. What it says is: You think it's your house. Well, we're taking it over.

Wednesday 13 June 2012

Ice cream

An early train to London to get to the RCA where I am running a guest project. It's flattering to be asked and sheer curiosity tempts one, so six days ago I went down with a project devised for three time slots.

I have been reading Wallace Stevens recently and The Emperor of Ice Cream was running in my mind so I came up with the idea of ice cream. First of all, Stevens's ice cream, as here:

The Emperor Of Ice-Cream

Call the roller of big cigars,

The muscular one, and bid him whip

In kitchen cups concupiscent curds.

Let the wenches dawdle in such dress

As they are used to wear, and let the boys

Bring flowers in last month's newspapers.

Let be be finale of seem.

The only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream.

Take from the dresser of deal.

Lacking the three glass knobs, that sheet

On which she embroidered fantails once

And spread it so as to cover her face.

If her horny feet protrude, they come

To show how cold she is, and dumb.

Let the lamp affix its beam.

The only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream.

We read the poem, roll it round our mouths, at least I do, then we read Helen Vendler's prose interpretation, here, in which she imagines it as a prose narrative. Then compare the prose narrative with what happens in the poem, concentrating, to begin with, on lines 2-5, those concupiscent curds and this wenches 'in such dress / as they are used to wear' and see where that language hails from, so we might enter the poem as a poem. We talk about Stevens's 'gaudiness' (his own words), and see how far we might be able to use language as a poet might use it, with all its dimensions.

Then I bring it an excerpt from Huysmans' Á Rebours where the aesthete Des Esseintes attends to his liquor cabinet that also serves as an orchestra:

He made his way to the dining-room, where in a recess in one of the walls, a cupboard was contrived, containing a row of little barrels, ranged side by side, resting on miniature stocks of sandal wood and each pierced with a silver spigot in the lower part.

This collection of liquor casks he called his mouth organ. A small rod was so arranged as to connect all the spigots together and enable them all to be turned by one and the same movement, the result being that, once the apparatus was installed, it was only needful to touch a knob concealed in the panelling to open all the little conduits simultaneously and so fill with liquor the tiny cups hanging below each tap.

The organ was then open. The stops, labelled "flute," "horn," "vox humana," were pulled out, ready for use. Des Esseintes would imbibe a drop here, another there, another elsewhere, thus playing symphonies on his internal economy, producing on his palate a series of sensations analogous to those wherewith music gratifies the ear.

We read right to the end of the passage where he has to go to the dentist, discuss synaesthesia and ponder how far ice cream might serve as music. This, I am guessing, sounds a bit infantile to them but it makes decent conversation and in the end it produces results. The young are so anxious to be cool and, preferably, dry too. Life, on the whole, is less so.

I also hand them some texts covering The Ice Cream Wars in Glasgow as another possibility.

So today I was back to talk to them in small groups about their ideas. It turns out there is a considerable variety of projects, some more to do with ice-cream than others, but relatively free interpretation is part of the package. In two weeks time we'll see how the projects turn out.

In the meantime I am home, very drained. Tomorrow night life goes on in London again. I'll say something about that tomorrow morning.

Monday 11 June 2012

The rehabilitation of the far right in Hungary 3: Hijacking the culture

So here's a story that springs out of Trianon, Transylvania, the nostalgia for the thirties and the move towards the far right.

The story tells how the Hungarian government requested that the ashes of János Nyírő, a Hungarian writer born in Translyvania, should be reburied in the place of his birth, a village that has been part of Romania since 1920. The Romanians refused so, according to one Hungarian paper, a strong right wing supporter of the government, a government minister, the Transylvanian poet Géza Szőcs (a poet I once translated) arranged for the ashes to be smuggled into Romania and for a surreptitious commemoration service to be held, addressed in strong Hungarian patriotic terms, by László Kövér, Speaker of the House. This didn't make huge headlines here but it was certainly seen as an act of provocation by Romania. Why would that be? Because such assertions of Hungarian sovereignty on Romanian territory are perceived as acts of aggression.

Who was Nyírő? He was a Hungarian Transylvanian writer who was a member of the fascist Arrow Cross, and represented them in parliament through their reign of terror in the last phase of the war, after which he was accused of war crimes and went into exile, where he died. There is no English language Wiki entry on him (though there is a Hungarian one) and I can't find his work on the web, certainly not in translation. Here however is a decent length article about him and the issue of the reburial. His writings have been available in Hungarian since 1990.

In some respects he resembles another Hungarian writer Albert Wass, who does have an English language Wiki page which has, it seems, been subject to some wrangling. He too has been accused of war crimes including murder.

Both Wass and Nyírő were recently introduced into the school curriculum by the government. The reasons given were that they were popular and representative authors of the time, and that their work was to be detached from their politics.

But their introduction into the syllabus is itself a political act, one of many successive acts of the government intended to replace people in cultural positions with its own supporters and to squeeze artists of a different political leaning into silence by directing public money away from them, towards its own preferred figures.

As Compendium, a review of Cultural Policies and Trends puts it:

The government has also set about making major changes in the cultural arena without a detailed strategy paper. The main underlining aspect of these developments is rationalisation by strengthening the position of the state.You can, as they say, say that again. I have in the past referred to the January article in The Independent that talked of a Kulturkampf. More recently the Financial Times, that bastion of left-liberalism has been writing critical articles, and reviews like this. And here is a Wiki sandbox article relating the story of museums and amalgamations (readers of Krasznahorkai may note a reference to Krásna Hôrka castle at the end.)

*

Introducing writers like Nyírő and Wass onto the syllabus, along with another, more major right wing writer Dezső Szabó, will be presented as an act of political and literary redress, but, in the Hungarian context, it is more worrying than that. Such powerful symbolic acts signal a dramatic change of cultural and political climate.

Hungarian history is problematic, and I haven't even mentioned 1956 or 1989. It is the 1930's that matter most here. It is the thirties that are being conjured and spread before the country as a model of identity, not so much Back to the Future as Forward into the Past, a past of conformity, xenophobia, authoritarianism, discrimination, hatred and fancy-dress patriotism with a distinct whiff of disaster.

The rehabilitation of the far right in Hungary 2: Trianon and the 1930s parallels

'No,no, Never!' Anti-Trianon picture card

The rehabilitation and, increasingly, the canonisation of the Hungarian Franco, Admiral Horthy, is part of the desire to return Hungary to the condition of the thirties.

What was the condition of the thirties? I want to go into this just a little since it helps explain the parallels. Please bear with me.

Following defeat in the Great War, Hungary underwent enormous political turmoil, the country's borders undecided, the old Austro-Hungarian empire in tatters, and conflict continuing on every side. The first political response was the so-called Michaelmas Daisy revolution that established the liberal-left Hungarian Democratic Republic at the end of October 1918, which was succeeded, a few months later, by a Bolshevik revolution that declared a Hungarian Soviet Republic in March 1919. In the August of that year the Romanian army invaded from the south and the Bolshevik leader, Béla Kun, fled the country, eventually to be executed in a purge in Moscow some time in the 30s.

The traumatic treaties of Versailles and Trianon followed. The country's geographical area was reduced by close to three-quarters which removed some 60% of the pre-1919 population, including a third of the country' s ethnic Hungarians who now found themselves in hostile territory. The greatest loss was Transylvania (my mother's birthplace) which was handed over to Romania.

That - apart from a period of five years by the second Vienna Treaty when, under pressure from Hitler, a part of Transylvania was ceded back to Hungary - is how things stand to this day. The light green part of the map below is present day Hungary, the darker free the Hungary of the pre 1919 period. The red segments represent the percentage of the ethnic Hungarian population in the area in 1910. The situation was, of course, chaotic.

Once the Romanian army withdrew to its new borders, the Hungarian military, led by Admiral Horthy, took over. The Soviet Republic had executed some 600 people during its whirlwind rule of 'red terror'. A 'white terror' followed. Under Horthy it is estimated some 5,000 were executed and some 100,000 people left the country. Jews were directly associated with the Bolshevik revolution and faced particular dangers including exclusion from work and university places, where a quota was applied.

The thirties consolidated this state of affairs. By the end of the twenties the economy had been stabilised but there was no minimum wage and the working class was desperately poor as were the rural workers who still lived in peasant conditions. The Crash of 1929 resulted in a further shift to the right and a desire for a one-party state. The country moved closer to Hitler for economic advantage and by 1939 the Arrow Cross party, the forerunners of today's Jobbik received the second highest vote in elections.

*

Key to this was, and remains, the issue of identity. The very existence of Hungary, with its isolated language and flexible borders, has always been under both real and psychological threat. The question was addressed by Admiral Horthy by the encouragement of whatever could be deemed to be 'Hungarian values'. These included a fancy-dress mentality, a kind of designer national-costume-and-uniform patriotism.

According to this view Hungary's troubles were invariably of foreign manufacture - and indeed, in a country whose fate had been governed by Turkey and Austria for almost four hundred years, in some ways they were - the most conspicuous 'foreigners' 'on site' being the Jews, whose activities had to be ever more firmly controlled.

There was a great patriotic cause too in opposition to the Treaty of Trianon with its carving up of Hungary and, most acutely, the loss of Transylvania. The traumatic effect of Trianon cannot be underestimated. After World War II, under Soviet rule, the tensions between Hungary and Slovakia and Hungary and Romania seemed to be reduced, but this was only appearance. The tensions remained, and remain, as strong as ever.

So here are the parallels:

Externally: Present day Hungary under the political thumb of the EU, trapped in its economic sphere, with an earlier Hungary dominated by foreign powers, including those who imposed Trianon, trapped within a financial system not of its own making (with the bankers traditionally identified as 'Jews')

Internally: the nation's identity supposedly threatened by cosmopolitan liberals and left wingers in hock to ideologies and suspect programmes elsewhere (also identified as Jews).

It is 1919 and the only way out is to put Horthy back on his white horse. Meanwhile the old wounds of Transylvania and Slovakia continue to burn and sting, offering themselves as patriotic causes in which the nation may be united. After the instability of the twenties with the Crash at the end,we are seeking the relative quiet of the thirties when decent people knew what was what, knew who to blame, when the church was respected, and when governments knew where to look for help (Herr Hitler with his economy and his restoration of at least part of Transylvania). Time to get out the old national costume. And they do, they do! Just look at the jackets of the elected Jobbik members of parliament. Fascist chic:

The case of two Transylvanian writers Albert Wass and, particularly, József Nyíro, both recently introduced on to the school syllabus cannot be understood without this background. The next post will deal with them within the context of the attempted cultural changes demanded by Jobbik and supported by the Fidesz government.

Sunday 10 June 2012

The rehabilitation of the far right in Hungary 1: Horthy and the thirties

One can make a good case for valuing a writer by his or her writing rather than by their opinions. I have tried to make that case myself in the case of, say, Kipling, much as Auden wrote in In Memory of W.B. Yeats:

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and the innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feet.

Time that with this strange excuse

Pardoned Kipling and his views,

And will pardon Paul Claudel,

Pardons him for writing well.

It is, generally, anathema to ban writers for their inconvenient political views. I write 'inconvenient' aware that what might be a moral disgrace to one side might be a form of shining virtue on the other. It was in this way that some of the finest Hungarian poets of the post-war years were banned for what the state called 'bourgeois individualism'.

For some states, at certain times, it has seemed convenient to ban material that might carry the wrong sort of message. There were right things to say and wrong things to say, and if it wasn't right then it was probably wrong. But the message in poetry and literary fiction is not always easy to read. In literature, and the arts as a whole, the charge of bourgeois individualism related to an implied ideology rather than to something as clear as a 'message'. It was not what was said, but a wrong way of thinking and feeling. It called for re-education, possibly prison.

But the reverse position also applies in such societies. It is not a matter of banning alone but of introducing politically convenient material, not just into the market but into the educational system as an object of approved study. This is not be on literary grounds but because the work so introduced supports the desired ideology and, beyond that, encourages a certain climate.

Literary value in either case is a secondary consideration. Or rather, literary value is determined in terms of social value, or political convenience.

*

Since the election of the Fidesz government in 2010 Hungary has been determined to turn the political clock back to the thirties. Fidesz currently has no credible left-wing opposition, its only true opposition being the fascist party, Jobbik, that represents the third biggest power in parliament. Jobbik's programme is as fascist as you can find in Europe. Its members would be very happy sitting next to Greece's Golden Dawn, possibly even to the right of it. Jobbik is rabidly xenophobic, anti-Semitic, anti-Roma and has at various times had uniformed and armed militia.

Fidesz claims to be a centre-right party but uses Jobbik as a cover for its own extreme right tendencies. In any case the two parties can meet in their admiration of the Hungary of the thirties. Hungary's problems with the EU and the IMF are reasonably well known. The EU objects to elements of Fidesz's new constitution and the IMF is withholding money. Every second week Fidesz claims the crisis is over, then it all begins again. It's like old-fashioned operetta and would be very funny if the country were not suffering the consequences.

Fidesz's first political aim has, throughout, been the neutralisation of left wing or liberal opposition and to take over the legal and cultural apparatus of the country. It has gone about this in various ways, ways about which I have written before. The point of the exercise is, I believe, to re-orientate the country's own idea of itself and to set it on a base that puts national pride at the top of the agenda. But what are the objects of this national pride?

An idealised version of the Hungary of the thirties is one of them. The love affair with the thirties is demonstrated in various ways, most clearly in the drive to rehabilitate the figure of Admiral Horthy. Wikipedia has a relatively kind article on him though of course the right in Hungary feels even kinder, regarding him as a hero, depicting him in painting as the figure of righteousness, erecting statues to him, naming squares after him, with an occasional protest.

It isn't so much Horthy's precise position on the right wing spectrum that is at stake: it is the symbolic value of the political rehabilitation that is of real importance. It is as if Spain had decided to fetishise Franco or if Portugal rehabilitated Salazar.

The act marks, and is intended to mark, a sea change, a turning of the tide. For many it is a fearsome and highly significant tide...

More tomorrow

Friday 8 June 2012

Forced marriage

I read that the government is considering introducing a law banning forced marriage. Whenever discussion of this subject comes up it seems that only one party - the woman - is being forced. I asked the question whether or not the man was forced too. The very idea seems to have struck some people as quite unfamiliar. Following this, Linda and I had a good long telephone conversation on the subject. She had researched the subject and written on it for a Times article a few years ago. She gave me an account of what she discovered and the thoughts below follow on that..

Arising out of the conversation there seem be two major distinctions.

1) The distinction between forced and arranged marriage (as I understand it the former is an enforced version of the latter with some variants and differences.)

2) The distinction between the forcing into marriage and what happens within the marriage afterwards.

Is it possible on the basis of these distinctions that the proposed legislation is aimed at the wrong target, that the perceived disadvantage for the woman is not in the forcing but in the marriage arrangement itself? Linda and a few others have suggested that once the marriage has taken place the man may have greater freedom to enjoy affairs or simply female friendship once married while the woman is (always? often? in what proportion of cases?) confined to the house under the head-of-the-household, her mother-in-law.

Clearly, these cultural contexts are important. How far can or should legislation touch them? As regards the act of forcing, I wonder whether our European expectations of a romantic marriage, that in the great majority of cases involve the man proposing and the woman having the choice of accepting or rejecting, are offended by forced marriage because it removes the prerogative of the woman to accept or reject.

In other words we may be perfectly prepared for a man's offer to be accepted or rejected (that's his lot) whereas we are unprepared for a woman not to be allowed the choice (that's her right). The man, as a potential proposer in traditional European practice, has no right to receive any particular answer: the woman has a right to whatever answer she chooses.

Is that why the conventional Western response to forced marriage concentrates entirely on the woman, to the extent that the man forced to marry her is either non-existent or even party to the arrangement. He is never even mentioned.

Maybe his rights and feelings are of no importance because he is assumed to be likely to enjoy more freedoms in the marriage once it has taken place. Maybe so. But it is curious never to hear of the other party in a forced arrangement.

Here, however, is an article from today's Guardian that tells it from the man's angle. I note he has a Hungarian wife.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_120601071935.jpg)