Monday 31 August 2009

To be precis(e)

I know this is silly but it amuses me. They are exam-proof book summaries. Five examples. I found them here (authors credited on link.)

1. A CHRISTMAS CAROL

Ebenezer Scrooge: Bah, humbug. You'll work thirty-eight hours on Christmas Day, keep the heat at five degrees, and like it.

Ghost of Jacob Marley: Ebenezer Scrooge, three ghosts of Christmas will come and tell you you're mean.

Three Ghosts of Christmas: You're mean.

Ebenezer Scrooge: At last, I have seen the light. Let's dance in the streets. Have some money.

THE END

*

2. WUTHERING HEIGHTS

Lockwood: I think I'll stay here. Tell me a story, woman.

Nelly Dean: I'm no gossip, mind you, but this guy Heathcliff got adopted, everyone hated him, and his love Catherine died.

Heathcliff: NOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO! (dies)

Lockwood: I'll be on my way.

THE END

*

3. THE COLLECTED WORKS OF JANE AUSTEN

Female Lead: I secretly love Male Lead. He must never know.

Male Lead: I secretly love Female Lead. She must never know.

(They find out.)

THE END

*

4. BEOWULF

Hrothgar: Let's build a big old dining hall and call it Herot.

(They do. Then Grendel, an ugly guy, takes over Herot and eats people. Beowulf rips his arm off.)

All: You rule, Beowulf.

(Some people make SPEECHES and tell IRRELEVANT STORIES. Beowulf kills some more STUFF.)

Beowulf: Wiglaf, I'm dying. See that my funeral pyre fits my greatness.

Wiglaf: Ok.

THE END

*

5. THE RIME OF THE ANCIENT MARINER

Ancient Mariner: I am creepy and old. Listen to me.

Wedding Guest: I'm late, but I'll listen.

Ancient Mariner: I killed an albatross. Then everyone died.

THE END

*

Bonus for getting this far:

6. METAMORPHOSIS

Gregor Samsa: Holy crap, I'm a vermin thingie!

(He DIES...eventually.)

THE END

Shakespeare and Company - two photos

I found these on the web, here. It's nice to keep them and be reminded. I'll be back.

The wall in the photo below is where George Whitman likes people to leave messages. Do check the photographs of the other bookshops via the link. And mind the hairless sphinx cat on your way through.

*

I am reading through the many entries for the Stephen Spender Poetry Translation competition for which I am one of the judges. As ever, when reading a great deal at once it is the oddment, the bold move, the slightly piratical or the eminently simple but perfectly balanced that stands out. This isn't fair on the merely very good. It is like looking at the smaller paintings in the Royal academy Summer Show. Hardly an inch between them.

*

The books I have read while away are:

1.) Henry Sutton's yet-to-be published novel Get Me Out of Here. Since it isn't published yet I can't say anything about it here, except that it is compulsive, disturbing, funny, scary and remarkably well constructed;

2.) Jim Riordan's memoir of his communist days in Moscow, playing (twice) for Moscow Spartak, Comrade Jim;

3.) Mark Sarvas's Harry Revised;

4) Adam LeBor's dark post-1989 thriller, The Budapest Protocol

All enjoyable. All recommended.

Mark Sarvas's is a quest book, in which Harry, a gormless doctor whose socially superior and somewhat smotheringly loving wife has just died, sets out to rebuild his life by way of Victor Hugo's The Count of Monte Cristo. It could easily have been a simple and rather dull story, the case of a seven stone psychological weakling who goes on a Charles Atlas-Dantés course of dynamic tension and finally kicks sand in the bully's face, but it is much better than that. Essentially it is about the nature of what appears to be a good marriage. It is sharp on social class, and best of all, on the complexities of love and control. The main story is not really where it's at. It is the dead wife who provides the most substantial material. She is the lodestone of the book. The true quest is not about the doctor at all: it's the voyage into the wife. That's the better book.That is why I read it.

Adam LeBor gets something very right in his understanding of the political mindscape of Hungary. That is where the power of his book lies. As a thriller it does thrill very well, particularly through the first half of the book where everything is still implicit. LeBor imagines a far right coup and its temporal and international dimensions. He registers the underlying brutality of a perfectly real nationalist mood that looks to make the Roma scapegoats for everything (the Roma first and then the Jews of course). The webs of conspiracy are finely spun: the spiders appear at the end. I'm not really a reader of thrillers, and I don't think I read this book exactly as a thriller either. Something in me always reads a little against the grain. I suppose I just look for what I want to find.

I didn't quite find it in Jim Riordan's memoir, friendly and enlightening as it was about working class life in Portsmouth after the war. He is very good on the fiercely antagonistic sense of us against them, where them is the bosses or the middle class. He joined the Communist Party early and stuck with it through 1956 and, as I remember, 1968 too. He is good on CP tensions in those times. He did his national service as a listener-in to Russian broadcasts then went to Moscow to the international Party school. He got to play for Spartak. All this is good story and interestingly privileged point-of-view. But there is, throughout, a sense of something withheld, something not quite true about the inner level of perception. In the end he tells it as yarn, but - going against the grain once more - I dont see it as yarn, but as a spiritual history that remains untold. A bluff. What did he really think of 1956 or 1968? He seems remarkably blithe about everything. Sorry. Don't believe it. Not sorry I read it. Not at all. But I simply don't believe it where it matters. Playing for Moscow Spartak? Yes, that's no doubt true, but it doesn't matter.

Sunday 30 August 2009

Sunday night is... Calloway and Boop

The pleasures of living in a metamorphic world in which everything is a haunted pun. Calloway turns into Michael Jackson into a dancing walrus and everything else turns into everything else. Keep the children far hence. Ah, home sweet home.

ps Some blog comments come in so late they feel like comments made to an empty room when everyone else has gone. I don't know why this is. I try to answer them - most recently Hayley in the Teechers' post some time back. I get an email to say I have an unmoderated comment, one that refers to months ago. They are generally perfectly good. Hayley's came in five minutes ago. Apologies, Hayley. Not my fault.

Saturday 29 August 2009

Home again

The weather cooled this morning. Alarm set to 6 am after a late-ish last night supper with with Laci, Gabi and Linda in the garden of a newly re-opened restaurant situated in the fork of two roads. Back for watermelon and a little talk before bed. At night car alarms go off, police and ambulance chase each other down nearby main roads and I wake at 5.30 anyway. On TV Tottenham are playing Liverpool in 1995. John Barnes scores. This is not a dream. The alarm does go off at 6am. We rise, shower, breakfast and pack what's left to pack, then tidy the flat. At 7 am we cross the hall to share a coffee with Laci and Gabi. The advance copy of The Burning of the Books and Other Poems, we have discovered, has a double blank page in it between the contents page and the first poem. C and I fill it, she with a drawing and I with a poem. We give it to them. Then the airport shuttle service arrives and the farewells.

The bus heads first into the Castle District to pick up a young Japanese couple. We cross Erzsébet híd (Elizabeth Bridge) with my favourite view of the Danube, looking towards Parliament and Margit híd (Margaret Bridge), a view I always find heartbreakingly beautiful. The main road to the airport is blocked by a three-car crash, says the radio, so we take an alternative road, Üllöi út, lined with plain single-storey buildings and a tramline along which we see no tram moving. We arrive at the airport, Ferihegy 1. There I continue to read Adam LeBor's thriller, finishing it on the plane, which has a bumpy ascent and a bumpy descent through cloud in both cases. The luggage belt take twenty minutes to start moving. Taxi drives us through back lanes to Hitchin. I forget how beautiful, green, and gently undulating Hertfordshire is. We have lunch at C's mother's where we left the car. Her forgetfulness is quite marked now.

*

Impressions of Hungary in political terms? Worrying, brutal, the country swerving far right rather quickly. Adam's novel explores this rightward swing in terms of a conspiracy thriller. The thriller part is fine - I don't read thrillers on the whole - but the political landscape he draws holds me right through.

Political landscape is an important aspect of the book's, any book's, reality-sense. It's always the reality-sense which grabs me. I am not primarily a great fan of plot and character. I take them in my stride, but consider them chiefly as the necessary, and necessarily artificial, means of shaping the reality-sense, the sense that tells me life is strange yet parallel. Truth to tell I generally finish up not caring what happens to the central characters as such. It is the world I want to understand not them. But since the world necessarily involves the imagination and cannot be understood without it, fiction, and therefore plot and character, are necessary. Reality-sense is not detached from the quality of writing, of course. The two are indivorcible.

It was Pound who said that technique was the test of a man's sincerity. I don't think he meant slickness, or effectiveness in terms of rhetoric. I think he meant a proper tension in the way language passes through a writer's nerves.

Well, Hungary works through my nerves and at the moment it chiefly makes me twitch. It feels as though it is at an important and dangerous stage in its development.

Friday 28 August 2009

Evening in the hills

Yesterday evening for supper with Elizabeth Szász and Miklós Vajda. L and G drive us over to Miklós's house, a little way further up the hill, away from town. Miklós is seventy-four now . There is a painting, by Tibor Csernus of him and two other literary figures of 1954 or 1955, titled Három lektor (Three Readers).

.jpg?)

He is the one on the left, aged twenty-four. Next to him is the critic Mátyás Domokos and the editor and published Pál Réz, all three to become important figures in Hungarian literature. I don't think Miklós has changed very much except in years and the effect of years. The expression in the painting recurs. He has been through a series of half-bodged operations for heart and hip and now walks with great difficulty. One day, when I have the time, I must write all this in proper detail. Enough to say both C and I feel a deep love for him and it is hard to see him in pain.

Elizabeth has become a kind of late companion for him, caring for him. She lives even further out in the hills, where there is practically nothing but hill, dense foliage, fruit trees and crickets, not so as you'd know anyway. Sitting there is like sitting in a forest. It's a modernist flat in a modernist block, as it looks from the front, but you have to descend a long flight of stairs to get to her level, wedged into the side of the hill. Over the next hill the observation point of Jánoshegy (St John's Hill), the highest hill in Buda, is just visible, yet close by. The half moon starts in a dusky sky then brightens and disappears behind clouds. No noise apart from crickets. The observation tower glows amber yellow, like a lighthouse for moths.

Elizabeth was born in England and first came to Hungary in 1962 and soon married the writer Imre Szász who died in 2003. I suppose Elizabeth might have been described as county in the old days. Boarding school, riding, swimming, Whatever the case she would have been strikingly beautiful and still is. A sort of Joanna Lumley of the East. She has lived here through the slow relative liberalisations (that is after the savage repression and retributions) of post '56 revolution, the further economic liberalisations of post-68, the cold cold war of the seventies, the goulash communism of János Kádár, the decline and fall of Kádárism and of communism generally, and now watches the rise of the far right with a kind of patient apprehension. She still swims in the Danube when she can and goes riding. Life here is full of these incongruous stories. Miklós too is a handsome man, a gentleman-citizen. More than a nobleman. A noble man.

We sit and talk about the situation here which is deeply depressing, about language and the fecundity of Hungarian swear-words. I suggest that the preponderance of curses involving mothers is a product of Catholicism which is why there isn't very much down that line in Britain. It may be so, it may be so.

It is so beautiful though. We sit and eat on the dark terrace with only the light of the room behind for illumination. It has been hot and muggy but the air begins to clear, even grow a little cool close on eleven.

I am back with Márai. Pushing on.Reading chunks of Adam Lebor's novel, The Budapest Protocol, in the necessary breaks. It's a dark thriller, all too close to the knuckle here. The facts and possibilities, I mean.

Thursday 27 August 2009

Memento Mori

I really don't know why I forgot to mention this as part of the excursion to Gödöllö. We stopped off at Vác, a small, elegant town to the north west of Budapest specifically to see the museum of unearthed coffins and mummified figures from the eighteenth century. They were discovered, well preserved, in a crypt of the old Dominican church. The conditions had somehow contrived to keep the clothes, the shoes, the ornaments and, in some cases, the very skin of the bodies fresh.

Comme ça (look away now if squeamish or superstitious)

It's not creepy - it is human and sad and touching to see the ribbons and baubles and rosaries and tiny slippers, and the care with which the coffins were painted in blues and browns and green, often the usual motifs but also brief legends about age, station in life and reputation. I hadn't realised that rosaries from the Holy Land (and many were brought from there) interspersed tiny hands and feet among the beads. The stigmata.

Outside is a big church with a large square before it where people were setting up for a concert later that evening. We nipped into a cafe that specialised in versions of chocolate as drink. We all opted for something different and took a taste of each other's. It was all delicious, a small bitter-sweet sensuous melting.

Death and chocolate. The perfect combination. Must go back.

*

This morning into town to coffee with Adam LeBor. It is rather surprising that we had never met before, but we had corresponded briefly. Now it was a cafe on St István körút (ring road). After a few minutes of slight awkwardness the talk ran to historical and current matters. He has been here since 1991, a Kilburn boy. We talked about the rise of the far right and how the corruption and nepotism in the current (socialist, alas) government has more or less destroyed any left-leaning opposition to FIDESZ the main centre-right party who will form the next government. But the far right is rapidly expanding, not among the old fascists but the young. Their websites are superbly arranged, says Adam. We both agree that we are very much living in the continuation of 1989 by other means. The poverty in the east of the country is very bad, he says. We exchange books and agree to have dinner next time.

Now home. Out tonight for dinner with old friend Miklós Vajda and Elizabeth Szász. One more full day left after this. Beside translating also dealng with post grads back in England. My schedule when I get back looks a little frightening.

Wednesday 26 August 2009

A little Márai from Budapest

There is no rest from work, of course - it's just a different environment as far as that is concerned, and in any case, time rushes on, unforgiving as ever. This morning, first thing, we walked down to the park and bought a few necessaries from the nearby store before walking back up the hill. Hot again, but Városmajor Park is shady. A concreted and fenced games enclosure for football or netball or basketball, is deserted today. There is also a large children's playground full of children and young mothers, some of them from the Far East. A troupe of schoolgirls are running round and round the park, their ponytails flailing behind them. C wonders whether they are member of a girls' football team. I say they all look almost exactly the same, the same willowy figures, roughly the same height. No doubt they will all be beautiful with sparkling teeth and diplomas. They move at a slow pace with a few in the vanguard and some stragglers plodding behind.

Back in the late eighties and early nineties itinerant labourers - often Romanians - would sleep and shave and spend part of the day here. The tramline skirts the park on the broad boulevard side. There are a few of the old sitting on benches or shuffling down the paths. I wonder whether I'll be one of those in ten or twenty years. My mind feels only about twenty-one. It's not ready for that.

But back to Márai. It is now the servant girl, Judit, telling the story. We find her in a cheap hotel room after the war, after the communist take over, with a young lover, a drummer in a band, who quietly exploits her and sells her remaining things with her full knowledge. It is the twilight of her beauty now. Her account of her old employers, including the young man who became her husband for a while, and whose story we had heard before, is far less focussed on abstract issues. It is packed with material detail and some penetrating insights into the mentality of their class. It feels like a bucket of quite welcome cold water after the intense introspection of the ex-husband. So she speaks:

The rich are very strange, darling. I myself was pretty rich for a while, you see. I had a maid to scrub my back in the morning, a car, a convertible coupé, driven by a chauffeur. And I had an open sports car too in which I raced about… And, believe me, I didn’t feel embarrassed to be moving among them, I was not retiring or bashful, I tucked in. There were moments I myself imagined I was rich. But now I know that I wasn’t, not really, not for a second. I simply had jewels, money and a bank account. All these I got from them, the wealthy. Or I took it from them when I had the opportunity, because I was a clever little girl. I learned in the ditch, in my childhood, not to be idle, to pick up whatever lies to hand, to smell it, take a bite of it, and to hide it, hide everything that others threw away… a enameled pot with a hole in it was just as valuable as a precious stone… I was just a slip of a girl when I learned that lesson: you can never be too industrious....

...Everything went as smooth as clockwork. The staff rose at six in the morning. The ritual of cleaning had to be as religiously attended to as mass at a church service. Brooms, brushes, dusters, rags, the window-cloths, proper oils for parquet and furniture; the fine wax with which we treated the floorboards, which was like those highly expensive egg-based preparations beauty salons produce for glamour girls… nor must we forget the exciting machinery, like the vacuum cleaner that did not merely suck the dirt from the rugs but brushed them too, the electric polisher that buffed the parquet so bright you could see your face in it, so I used to stop sometimes and simply gaze like those nymphs in the ancient Greek reliefs… yes, I’d lean over to look at myself and examine my face as absorbed, as startled, my eyes sparkling, as that figure of half boy-half girl of Narcissus I once saw in the museum looking adoringly at his charming ladyboy reflection…

Each morning we dressed for cleaning the way actors do for a performance. We put on our costumes. The manservant put on a vest which was like a man’s waistcoat turned inside out. Cook was like a nurse in an operating theatre in her sterile white gown, her head covered in a white scarf, waiting for the surgeon and patient to turn up. I was like one of those peasant girls in the operetta chorus dressed for gathering berries at dawn in my traditional maid’s cap... I was obliged to understand that this dressing up wasn’t simply because it was pretty but because it was hygienic and clean, because they did not trust me, fearing I might be dirty and carrying a lot of germs. Not that they ever said as much to my face, of course!... And they may not actually have thought it, not in so many words… It was just that they were wary, wary of everyone and everything. That was their nature. They were suspicious to an extraordinary degree. They protected themselves against germs, against thieves, against heat and cold, against dust and draughts. They protected themselves against wear and tear and tooth decay. They never stopped worrying, whether it was about their teeth or the state of the furniture, about their shares, their thoughts, the thoughts they adapted or borrowed from books. I was never consciously aware of this. But I understood that from the moment I first stepped into the house they wanted to be protected against me too, from whatever disease I carried.

Why should I be carrying a disease?... I was young, fresh as a daisy. They even had me examined by a doctor. It was a horrible examination; it was as if the doctor himself did not fancy it. Their local doctor was an elderly man and he tried as best he could to joke his way through the minute, painstaking process… But I felt that as a doctor – indeed the family doctor – he essentially approved of the exercise… there was of course a young man in the house, a student, and it was not unlikely that sooner or later he would want to get familiar with this kitchen-maid straight out of the ditch. They worried in case he caught tubercolosis or the pox off me… in other words I felt that this intelligent old doctor was faintly ashamed of this over-scrupulous need for assurance, this just in case. But since there was nothing wrong with me they tolerated me in the house like a decently bred dog that would need no vaccinations. And the young gentleman did not contract any infection from me. It was just that– much later – he happened to marry me. This was the one danger they never thought to insure themselves against. I suspect that not even the family doctor anticipated it… You have to be so careful, darling. I think the old gentleman, if no one else, would have had an apoplectic fit if it ever occurred to him that a disease might be transmitted in this way.

More later.

Tuesday 25 August 2009

Party out

Grateful thanks to the splendid Mick Hartley who has posted this so that I could pinch it:

Tuesday is hereby proclaimed to be Sunday, Wanda Jackson day.

*

The Palace at Gödöllő looks like this:

It has powerful connections with both Hungarian independence and the establishment of the Dual Monarchy, through Count Andrássy and then the wife of Franz Joseph, Elizabeth of Bavaria, Empress of Hungary, reputedly the most beautiful woman of her time, later assassinated, at the age of sixty-one, in 1898. She was reputedly good and kind and learned Hungarian well before she needed to, and as a result the Hungarians love her.

Yes, but... It's the usual yes, but.. in one way complex, in another way very simple. Take the simple one first.

The sheer extent, opulence, extravagance of the palace is nauseating, especially when you have just seen photographs of the 30s Depression at the Crisis exhibition I talked about two posts ago. It is hard to hold the images together. Half of me says: Burn the thing down! Écrasez l'infâme!. The other half say: Hold it. Wouldn't it be better to leave it as it as, but include a mass of notices saying: Here died the footman, Albert X, or: Here slaved the laundress, Maria Y. Record the existence of all those unrecorded in the grand annals, not depicted in the oil paintings. Let them be present and let that be the rebuke. Not so much of those who are noted and celebrated here, but to the world that produced them. Who cleaned the privy? Who died falling off the scaffolding?

The more complex Yes, but... refers to the other argument, which is to do with the beautiful things of the world. The beautiful things of the world, it says, require wealth and leisure to commission, produce and display. That much admired altarpiece for the private chapel, that ravishing tapestry above the bed, the great classical orders in the portico, the frescoes, the furniture, and that whole range of artefacts from delicate frippery to towering masterpiece. Would we have had them or - let's raise the stakes - the Sistine Chapel ceiling if there were no Sistine Chapel, no Rome money? It is hard to deconstruct Michelangelo's Last Judgment purely as the ideological product of a ruling elite. One might be missing something. What of the great cathedrals? And so on down the Kenneth Clark Civilisation line so fiercely opposed by John Berger.

I don't know the answer to that one, except that that was then. Let's try do things another way now, not just for show, not for the sake of Popular Art. Not Cool Britannia Art. Not Big Business Art (nor Big Ideology Art). It shouldn't be impossible. It should be in the nerves somewhere. And truth to tell, much of the art in the palace at Gödöllő is hideous trash.

Monday 24 August 2009

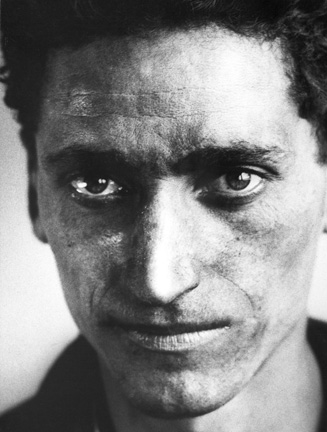

Capa

Ruth Orkin, Robert Capa in a Café, Paris, France, 1952. © Photograph of Robert Capa by Ruth Orkin

That's his face above. And it is quite a face. From the wild bohemian boy to the smoothie with the thick brows and the James Bond smile set to 'quizzical'. A handsome rogue.

Speaking personally I don't think it's the worst thing to be - a handsome rogue, that is - and if I had been granted the necessary equipment in terms of features I might have tried to make a go of it. But then he was a brave and handsome rogue, and that is a more challenging package.

'So what's this photography lark like?' he asks the already established photographer, Eva Besnyö in Germany in 1931 or so. She tells him it's not a lark but a profession. He flits around, gets himself a job at a photographer's and learns the craft, then tries to set up as a professional himself. At that stage he is still Endre or André Friedmann, a Budapest-born Jewish boy who studied politics. He is ultra easy-going and jokes all the time, quickly charming even those who tend to be suspicious of precisely such untrustworthy characters. He gambles too. He gets his first break in Denmark after hearing Trotsky is in Copenhagen to deliver a speech, and while all the photographers are elsewhere he snaps the famous man in action and sells the pictures. At last he is a photographer. But it's still difficult. Then, in Paris, he meets a very beautiful young refugee from Leipzig called Gerta Pohorylle who acts as his entrepreneur. They both change their names. She to Gerda Taro, photographer, and he to Robert Capa. That's about 1936.

Soon he is off. He photographs the protests of the Front Populaire. Spain next, the Civil War, where he takes that famous picture on 5 September 1936 of the first victim of battle. This one:

Today there are all kinds of controversy as to whether it is a set up, a pose. If not, he is very close indeed. 'If it's not good enough that's because you're not close enough' he says. (There are more photos in the series of the dead Republican soldier, complete with name.) The rest, as they inevitably say, is history, or at least war history. He becomes the man to send to the next war zone. He lives it up and takes the chances. Inevitably perhaps, in the end, he steps on a landmine in Indo-China and is killed instantly. It is April 1954, just a couple of years after the top photo was taken. In the meantime there is Picasso and Matisse and Steinbeck, Normandy, Stalingrad etc.

*

I said I enjoyed the other photographic show more, but that is primarily for three reasons. Firstly, because I knew the work there rather less well than I know Capa's; secondly, because Capa's work is either war or cultural glamour, which is exciting but restricted; and thirdly, because, in some ways, the Alan Sekula view stands up rather better here. Not, I should hasten to add, because of Capa himself, but because of Capa's aura. He was not unwilling to cultivate an aura himself of course, albeit in a playful Humphrey Bogartish sort of way. It is, rather, the aura or glamour of early death. It is therefore not unnatural to say:' This scene is from such and such a period of Capa's life' rather than: 'This picture shows...'

Aura is a Walter Benjamin term used to define the alluring power of unique objects in an age of mechanical reproduction. Capa is himself the unique object in this case. He is unique in that what we know about him is a function of uniqueness. He is a myth, an icon, what you will. He looks at you a little cynically. Under his breath he is saying something like "We will always have Paris." Adding, "Or Berlin, or London, or Budapest, or Barcelona, or..." So the dying Republican soldier is part of Capa's story. Or also Capa's story. It would be hard for him to be entirely his own story now.

The Crisis exhibition showed people in unheightened states. They were ordinary days when people were doing tough, demeaning, boring ordinary things. No great event had overtaken them. Nothing haloed their worn bodies. They were simply a part of the vast and complex day, a day when other might have been listening to a choir or chamber concert at the great palace in Gödöllö where we called yesterday, or moving just that bit closer to the sniper for the sake of that better (no pun) shot. Some words on Gödöllö maybe later.

Sunday 23 August 2009

Photographs of an Approaching Crisis

Of the two exhibitions I preferred the international Things are Drawing to a Crisis (a slightly odd translation of the Hungarian Válságjelek, which is literally 'Signs of Crisis'). The accompanying newspaper-like handout begins by comparing the current world financial crisis with that of the Thirties, and while that is, I suppose, a natural enough analogy, it seems - on current evidence at least - too far fetched.

But this exhibition is about the crusading, social (and generally socialist, often specifically communist) activities of various photographers to document poverty and unemployment. There is a sentence of Alan Sekula's on the front page to the effect that " looking at documentary photography as a work of art is running the risk of making the subject almost invisible and taking the photo for an impression of the photographer's sensitivity and personal vision."

I fully agree it runs the risk, though I can't see how the risk can be avoided, and it is unlikely, I suspect, that the subject ever becomes completely invisible, as it might, say, with painting, where the artist is fully expected to be presenting a personal vision. There is no way of obviating the observer, or detaching him or her from the observed. There is the whole business of selection to start with - the photographer goes somewhere for reason, takes a lot of shots then selects from the contact sheet, according to certain criteria (in the case of the current exhibition it might well be Constructivist approaches to composition).

However, the subject stands in a special relationship to the observer (and consumer) in photography, because - and I have often argued this before - we the consumers, as well as the photographers, are conscious that at the split second light enters the camera there is an uncontrolled mechanical process of the kind painting doesn't offer. Which is one of the reasons why photographs may be admitted as records of events in court while paintings or, say, poems can not. The only way that I can see that a painting (or a poem) might be used as legal evidence is in a case where the painting or poem is itself directly the result of or producing some possibly illegal action (eg Is this painting what you say it is? or What is the seditious effect of this poem / painting?)

I don't want to argue all this now. It's only a blog-post after all, not an essay. Enough to state I thought this a marvellous exhibition in which formal values were at the service of a never-forgotten humanitarian cause. I could never overlook the sheer encounter with the real people at the far end of the lens. Every one was person first, compositional element second.

Who was in the exhibition? Well, a lot of Walker Evans, whose work I already knew and had in fact written about in the past, but the ones that move me most were Theo Frey, John Fernhout, the Hungarians Eva Besnyö and Kata Kálmán. A good half of the photographers were women.

Theo Frey: Radrennbahn, 1935

Kata Kálmán: Ernö Weisz Fabrikarbeiter, 1932

I'll try to get actual pictures up as soon as I can (best I could grab above), but it is impossible to look at these photographs and not think the figures shown dignified even in degradation. There are beautiful faces, plain faces, strong faces, weak faces, defiant faces and broken faces - and there are the faces of children as bright with life as the young of the healthiest, often children labouring in field and mine. They are all breathing the same air as the photographer.

And having noted and been moved by the self-evident dignity of the faces and bodies, however thin or broken or breaking, it then becomes perfectly natural to conclude that the photographers were right to align themselves as they did politically. Why after all should these dignified people be so much poorer than those others sometimes glimpsed passing by on their way to a theatre or cafe? What earthly reason can there be for such disparity?

It's really that simple.

In that way the polemic of the photographs is subtle, valid but powerful. I don't think we would necessarily think this after seeing an exhibition of paintings, not in the age of photography anyway. We know that there existed a moment when precisely these people, stood in those precise places, and were as alive then as we are now.

Ludwig Museum

From wild heat to long steady downpour. 20 August is traditionally when the weather breaks here, the stifling heat broken up by thunderstorms and a drop of some 10C. I write this early on Sunday morning from the flat next to our dear friends L and G (practically brother and sisters) the morning after the break in the weather. The first day - Friday - was a matter of C going to meet old friend over from UK, me doing some work translating, then getting travel tickets from the nearest major station, Moszkva tér, having a bite for lunch then hopping on a bus back up the hill. It being a public holiday we talked and talked with L and G. More work.

Yesterday morning I continued the translation but went for an hour to the studios of Klub Radio - a liberal-leftish station - to record an interview in Hungarian, mostly about my bilingual selected poems, Angol Szavak / English Words, but also about my Madách translation, a new edition of which appeared just a few weeks ago. It was a very friendly set up, a woman and a man handling the questions. To my surprise they asked me to read three of the poems in the Hungarian translations. I had never done that before and stumbled twice on longer words but on the whole it was fine. The questions were essentially of a biographical kind - stories being what they - and I suppose most listeners - want. Generally my Hungarian was all right though I am always aware I would be saying the same thing more precisely, with a more exact sense of its psychological weight, in English.

Back home we talked more and I did a little more translation before we decided to go for lunch in a restaurant at the hilly outskirts of Buda. The food was good, the waiters like somewhat surly professors of grammar, but a beautiful garden adds the necessary lightness.

Then out to MuPa, the Palace of Art, the Ludwig Museum part where there are two photography exhibitions - one of thirties social photography, the other of the life work of Robert Capa (Endre Friedmann). The new National Theatre stands just in front of the equally new MuPa and the contrast is startling. I can honestly say The National Theatre is one of the most hideous buildings I have seen in recent years. I can't get properly on the net in this room - the sporadic posting might be because of that - but a picture will be provided. I don't say this because of my political prejudices but, if my prejudices needed justifying this building would be all the justification needed. It is a folkish-postmodern gallimaufry that is all but pure Ceausescu, with so many 'eclectic' motifs that it reminds me of a particularly kitschy presentation of chocolates. The history of its building and siting is fascinating. More another time.

MuPa is a much more straightforward modern affair, grand but not showy, with a faintly boat-like theme, slender pilotis holding wide sweepingspaces. It has a seventies air but is altogether lighter, proper craftsmanship.

The exhibitions will be a separate post, following this.

Friday 21 August 2009

Budapest 1

The last night in Paris was beautiful, considerably better than the boiling day on which neither walking around or walking to anywhere seemed possible. So I read and read, then we went out for early supper at the couscous place recommended by Jemma, sitting out on the pavement. I was extremely flattered to have the waiter compliment me on my flawless control of at least ten French words. Accent without a trace of French is the ideal to aim at and I am getting there. Inspector Clouseau on a taciturn day.

After the meal we walk along the Seine, first along the upper embankment than back along the lower. There is a huge party of picnics going on down there, not the tourists but the French. The picnics are so crowded they run into each other. Some boys play guitars. Every party has wine. It's mostly the young, and mostly in t-shirts and midriffs, but by one of the bridges a group of six or so are smartly dressed, have put out two tables, covered them in white tablecloth and are doing the full Jack Vettriano, No butlers, but the sleek inheriting the earth.

It is all amiable and hedonistic, A polite carnival. We amble along then climb steps to watch rollerbladers and rollerskaters engaged in a night long performance of plastic-cup slaloms, dodging round the red row and the yellow row, dancing or dashing, on points, on heels. We find a bench and watch for an hour or so, dropping a coin into the hat. When I look out of the Esmeralda window at midnight they are still at it.

No sleep, or maybe half an hour at the end. The drag to Orly is a drag but manageable and not too far. Orly quiet. The announcements race through in French. Hard to understand.

Budapest suburbs look quiet and neglected, but flags line some avenues. The airport bus - on which we are the only passengers - goes the long way round. And there are L and G waiting at the door. We are installed in our flat. Later we inspect each other's childrens wedding photos. The fireworks begin and keep rattling on. Eventually bed. The night cool. I finish Mark Sarvas's book on the plane so now I have read all I have brought for pleasure. Notes to follow.

Wednesday 19 August 2009

From Paris 2

Same room in Shakespeare but hotter, in fact the hottest day of the year so far, about 38C in the shade. The best option this morning was a tour of the Seine by bateau mouche. The hot sun beat down but the breeze compensated and I had bought my umbrella so parapluie became parasol, only blowing inside-out once.

Our natural comparisons of the river-boat trip were with London and Budapest, both quite different. We remind ourselves that Paris wasn't bombed in WW2, also that its beauty and coherence is the product of what was an autocratic system. On the other hand the stones of the Bastille have gone to make one of the twenty-four bridges and the Louvre is no longer a palace but an art gallery. And it is beautiful and coherent. Ravishingly so on a good day. And, what is more, it is friendly, or has been to us wherever we have stopped for drink and food, the waiters jolly and welcoming. This morning the petit dejeuner at the cafe on the corner the young man practically danced between tables, grinning and joking. And a damn good petit dejeuner it was too - fried eggs perfectly done and the whole thing light, much lighter than an Anglo-Saxon breakfast. Of course it obviates the need for lunch, especially if we have it as late as we did.

My sleeping has been fitful to much delayed. Last night I was up till 3.30 am or so, now reading, now playing patience on my iPod. I have got through two books so far, on which comments later. I have found Mark Sarvas's book on the shelves here and have now bought it so it will be Budapest reading for me. Marilyn H also gave us her translation of Marie Étienne and I have started that. I can't really get on with too much necessary work here (it will be back to translating in Budapest) and it's a real pleasure to read without guilt.

The Vietnamese waiter last night was also full of larks. The only waiter in a place about the size of the average bathroom, high spirits and larking must be his shield against grinding dullness and madness. I remember noticing how the removals men fifteen years ago sang loudly as they carried our heavy cardboard boxes of books into the house. Distraction. Division of energy. One of the origins of song. The Uses of Beauty.

C had a delicious dish the waiter recommended for her, advising her against the one she first chose. One could take an uninvited recommendation as a touch bullying but the dish was so good it was a pleasure. I know I shared some of it (and C shared some of my duck as was only fair).

The ice creams here are perfect, especially the chocolate. Stop me and buy one the signs used to say. My advice: stop by any place selling ice cream and get the Berthillon chocolate, plus, let us say, passion fruit sorbet. Pick up an iced lemon drink while you're at it, solid with crushed ice.

Tips and tour guide from GS, only available at this blog. Tomorrow to Orly by RER and Orlyval - expensive! Then Budapest. But I like Paris. I want to live here for three years. All offers from wealthy patrons considered. Cheers M Gulbenkian. How you doing M Soros? Ah Mr Jameson, of the famous whiskey! May I be of service for a small consideration?

Tuesday 18 August 2009

From Paris

Writing this upstairs at Shakespeare and Company, the traffic flowing by outside. The reading yesterday went like a dream - quite dreamlike for me in fact - since it was outside, with a mic, to a very large audience that included Marilyn Hacker and the marvellous Romanian poet Denisa Comanescu who happened to be in town. Intent audience and lots of conversation afterwards.

Our first contacts were Jemma and Hilary who are working here, and Sylvia Whitman, daughter of 95-year old George who took the name over from Sylvia Beach's original shop in the rue de L'Odeon back in 1962. I expected Sylvia to be a middle aged woman at youngest but she is only in her twenties (if that, I almost add). She now runs this extraordinary ship of books and memorabilia. Heather (Ungvári) Hartley introduced my reading and led the questions afterwards. She is herself a poet and the Paris editor of an international US review - Tin House. Bought one this morning and read it, impressed. The magazine has quite a history. Her first book comes out very soon. cannot speak too highly of these people, and indeed of everyone in the place.

Jemma gave us a tour of the house this morning, all nooks and crannies, all filled with books and pictures and slips of paper. Finally we arrived at the top and had a brief audience with George himself, frail and in bed. At first I thought he was going to bawl us out (C & I) for not staying in the house itself. He has always been intent on making the house a place where writers stay and work then move on. And what writers! But Jenna explained we were being accommodated at the Esmeralda round the corner. George relented and smiled.

As for the Esmeralda, Jemma says it is the hotel Jeanette Winterson insists on staying in when in Paris and I can see why. C and I are in Room 18, top of the building, up several flights of winding wooden stairs. No lift, so a hefty drag of luggage there (very like my Sisyphus poem). The whole house is darkly floral from wall to ceiling. Narrow doors all rustic, some stained glass. Facilities are basic but clean. Our room is wallpapered in roses every which way. It's like sleeping in a bower. Even the lamp shades are in the shape of flowers. As you lean out of the window and look to the left you are in full view of Notre Dame which seems almost close enough to touch, parallel with the west front.

Downstairs sits a one-eyed elderly woman who is presumed to be the owner. We are keeping fit but going up down four floors of narrow winding stairs.

After this morning's guided tour, a walk over to the Places des Vosges, my favourite square of all, sitting and reading in the square itelf before taking a long light lunch in the cafe at one corner. Then stroll over to meet Marilyn H as arranged. She is up three flights of narrow winding 17th century stairs, which we quickly descend to have coffee at the cafe below.

It is hot but we walk generally in the shade. I have often been to Paris but not so much walkabout in recent years and the route we took - Left Bank to Marais - is a wonderful walk - Paris streets at their most intimate, elegant yet quietly restrained. Budapest is beautiful and blowsy. Paris is le bon gout almost everywhere.

As for the bookshop it is more an old galleon than a house. You almost expect Captain Jack Sparrow to come bounding down the stairs. A black dog and a white cat weave in and out of it. And books and books and books. Even a piano. And old armchairs. Bliss.

Sunday 16 August 2009

Sunday night is... Adam Faith

One of the first British stars of my UK youth, along with the earlier, rawer version of Cliff Richard (who was pretty good in Expresso Bongo, gorgeous East-End-Jewish agent performance by Laurence Harvey), not forgetting Tommy Steele, Marty Wilde, Helen Shapiro, Billy Fury etc.

Faith was, relatively speaking, a post-Buddy Holly pop intellectual, interviewed by Malcolm Muggeridge on TV about youth and sex and so on. Articulate and sleek. Later a good actor. Good with money. Died early at 63. This is a sixties reprise of a fifties hit. The hairstyle was greased and parted before.

Associations: a windswept seafront, the boarding house, Weetabix, mother too loud over breakfast, the amusement arcade, funny cowboy hats, the old Hillman Minx. Our neighbour E, who had run shops in her time, once said that running a shop was anxiety punctuated by boredom. That was Early British Childhood time for me. And it lasted a good ten years or more. I think I must have been mentally running a corner-shop tobacconist's.

*

Oh, and I forgot this amazing thing, sent to me by James.

A little like the famous film of Picasso painting live, but with a story.

To Paris and Budapest

Reading at Shakespeare and Company at 7pm on Monday, then staying a couple of nights before flying to Budapest. It's a privilege to read at the famous bookshop so I am very much looking forward to it. Founded by Sylvia Beach and now run by George Whitman's daughter, Sylvia.

I hope to be posting from Budapest - possibly Paris too.

Saturday 15 August 2009

Evil

While preparing for Paris and Budapest and trying to clear some space at my desk for R & H when they come to house-sit, I was listening to an interesting conversation on radio about the use of the word 'evil' to describe the killers of Baby P. What was it the Daily Mail (no link) had: Baby P killers unmasked: Evil mother who stood by as son was tortured... and the neo-Nazi boyfriend who abused him... sex-obsessed slob..

The discussion was good, meaning it was properly serious. One argument was that the evilness of evil acts had to be stated in absolute terms, not relativised or medicalised into a condition like psychological disorder. Responsibility is responsibility, and if torturing a baby is not evil then what is? The other argument was not in fact an argument, simply the articulation of a faint unease at the use of the word 'evil' because it implied possession by an external evil principle. It was, the arguer implied, too much a metaphysical term.

It was a serious discussion because there were no straw men in it. Both speakers were properly struggling with the relation of language to action. Or maybe it was to an event. It was an evil deed to kill the child, that was agreed by both, but were the people who did the evil deed, themselves evil? What did it mean to say that? Evil by nature? Evil only in that series of acts? Were they born evil? Did they become evil at a certain point? Is there a transition point at which people enter evil as they might a territory? And if they were evil now would they continue being evil? For ever? Was evil not just their current condition but an eternal condition?

Christian teaching is to hate the sin but love the sinner. But to love Tracey Connolly, Steven Barker and Jason Owen? On what spiritual eminence would one have to stand to declare positively that one loved them? Not on principle, but really? Oh best not say so. Best not declare it. If you do, if you can, you must do so silently and by action, anything else is betrayal of the word 'love'.

As for the word 'evil' I share some of the unease. I don't always trust those who use it readily. It is, if you like, a poet's quibble about metaphysics. But language isn't just an instrument like a mechanical digger for shovelling a pile of soil. I think there is a sort of obligation not to be certain about the great metaphysical terms. Very high stakes. Big mounds of earth.

And one good word for radio. The best of radio is wonderful. I can overlook any number of dreadful attempts at comedy or bad drama when it comes to hearing voices such as these.

A brief multiple choice on Picasso's Monster

The female passengers in the boat are:

a) In terror of the monster?

b) Calming / taming the monster?

c) Encouraging and inviting the monster?

d) Having enjoyed the company of the monster are sorrowfully beseeching it to stay?

e) Welcoming a visit from their mother?

I think it is quite important which, though it is possible that they are doing all five at once, or that the five states are constantly switching very fast between each other.

It is, I can't help noting, a fully breasted monster. However... What's the song? Sometimes it's hard to be a woman... Not so easy being a man either.

Given the boat. Given the sea. Given the weather. Given the tiny raft on which the monster is sitting and which seems very likely to tip over at any moment.

Friday 14 August 2009

New book plus: Rotterdam interviews & links, Mark Sarvas

I have just found these two links from the Rotterdam International Poetry Festival. I must explain that they are from the complete series of the festival and you will find marvellous poets from all over the world here, including Bei Dao, Piotr Sommer, Tua Forsström, Jacques Roubaud, Maura Dooley, Vera Pavlova, Umberto Fiori, Dunya Mikhail, Yang Lian, L.F. Rosen (whom I translated while there - I must submit those translations for publication somewhere!), Arjen Duinker, Luke Davies, Valzhyna Mort, Henrik Nordbrandt, Sigitas Parilskis, Kazuko Shiraisi, and Brian Turner - all either in recorded sound interview or on film, or both. It's wonderful to have them - particularly the films which I never saw while there. What a marvellous festival that was, and how well organised!

You'll find the 'me' bits among the others, scrolling up or down:

1. Sound Recording

In the half-hour recorded interview with Judith Palmer I talk about poetic responsibility, blogs, the simultaneous aspect of ritual and anti-ritual, constraint, rhyme and feeling and accident, the ornate necessities of poetry, one's own psychological predilections and self-image, the idea of packing material into poem being like packing a suitcase, on not telling language what to do, on catching things in flight, catching experience as it is in language and stopping time, memory as snapshot or short snip of film, other art forms including The Burning of the Books, poems as organic marginalia, works talking to each other or performing a duet, on self-deprecation providing it isn't lying, on being an under-educated art student, on lacking a sense of authority and diffidence, on affection for England, on writing in a second language you can never quite own, on writing in standard English, on having no memory of forgetting Hungarian / learning English, the provisionality of all language, language as an object, on synthetic memory, the game of memory and certainty, the midnight skaters, the disappearances and dancing of poetry.

I read two poems: Esprit d'Escalier from the New and Collected Poems and my earliest properly formed poem of 1976, At the Dressing Table Mirror, originally in The Slant Door.

Interview with Judith Palmer here, move to my name and click on it (also on sidebar now)

2. Film-clip

2. A film clip of some six and a half minutes, mostly interview and reading My Father Carries Me (from Reel). But this is a lovely series. It is great and moving to look at the clips of the others. I talk about how I started writing, about crossing the border into Austria, about terza rima, about memory again... I spent a lot of time particularly with Umberto, Piotr and Dunya...

The clips are here.

*

I also wanted to reciprocate Mark Sarvas's adding of my site to his links by adding his to mine. I should have done this long ago. Mark's site, The Elegant Variation, is one of the leading book sites in the USA. Chiefly concerned with fiction he gets through a vast amount of fascinating and superbly intelligent reading. He is here, as also in the sidebar under Writers' Blogs.

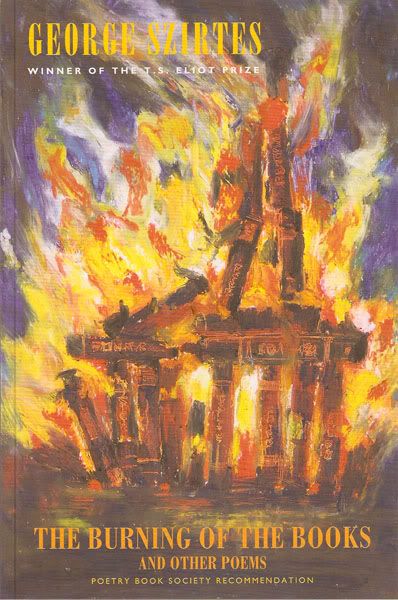

New book: New poem on front

Advance copies arrive of The Burning of the Books and Other Poems, due out end of September. A Poetry Book Society Recommendation. The Bulletin (written by Eva Salzman and Paul Farley) says:

The T S Eliot Prize brought George Szirtes to wider prominence as one of this country's leading intellectual writers... Both weighted and enriched by heritage, his is a European visionary and multi-disciplinary sensibility straddling time and dimension restrictions, mostly within strict forms, with a manifold awareness that renders disparate chapters of history contemporaneous with each other.

His prodigious technique is demonstrated by the structural narrative of the collection in its entirety, whereby the couplets and tercets regularly employed throughout bear fruit in the virtuoso canzones punctuating the groups of poems... part of a kaleidoscopic range of refrains and cross-references binding the different sections.

The new poem on the front is the third of the wrestling series. The whole series appears in the new book.

Thursday 13 August 2009

Limp response: a brief dispatch from the front

The Guardian (naturally) has an article about a new erotic magazine for women and is worried in case it is prosecuted if it shows the erect male phallus.

Naturally the Guardian women cry SEXISM!!!!. Why can men look at a woman's body, when women can't look at men's. Woman = sex object!!!

Actually, and I frankly don't mind pointing this out, women can look at men's bodies just as naked as they are. It is perfectly legal.

The question is of sexual arousal. Erection.

I propose that the picture of an aroused male sexual organ can only be properly compared to an aroused - please emphasise the arousal - female sexual organ. The rest is faux-sexism, in other words bollocks.

Forgive the short paragraphs but I thought you might like this tabloid.

The classical and terror

Picasso: Bull-headed Sphinx, Etching, 1933

I am not sure how Picasso does it. He takes the classical and he draws graffiti all over it and it's still the classical. Those four children's faces are clearly derived from the Greek model, the brow forming a single line with the nose. They have a clarity that is calm and unruffled even when faced by this extraordinary monster that seems to be of one body with sea and sky, all turbulence, all menace, all baroque curve and phallic aggression. And yet it too is calm. Calm as form. The composition is balanced.

The balance seems almost accidental - a kind of scribbled balance - but it's as if Picasso couldn't help but balance. Let everything be ruffled and furious and staring and even nightmarish: still it remains distilled. Distilled form is the core of classicism.

Distillation is an imperial cheat of course, a game. We know the world is not distilled into perfect form. We know the world's clumsiness and jaggedness. We understand splatter and squelch and droop and dislocation. But here we are: balanced, looking the terror in the eye and finding it too is balanced and distilled. He/she is like Rilke's famous angel, the one that serenely disdains to destroy us because its nature is serenity.

But how does Picasso do it? Can we, for a second, believe in the skeleton under the body? Can we make sense of the body at all when it looks like, say, this, or this:

The strange thing is that it is precisely the substructure that holds things together. But it isn't an anatomical substructure: it is a distilled substructure, a substructure of notions and ideas inside a code, as if the proportions of the body were immutable, permanently inscribed, carved into an ancient tribal language of psychological forms. And it calms us. It calms me anyway. I know, when looking at it, that real terror is only an imperfect copy of distilled terror, a distortion, a ballooning shape from a hall of mirrors. In other words art, or the spirit, or the imagination, or the 'rule' - that rule by which Matisse's luxe, calme et volupté remains alert and not merely sloppy, is stronger than death.

In a way.

In a very distilled sort of way.

So Picasso is both ugly and beautiful, both the terror and the distillation. And those four children aboard the lost ship are not the ones menaced. They are in control: Soyez douce, they say. And douce he is.

I prefer this to the myth of the lady and the unicorn. That lady has always been a bit too schoolmistressy for my taste.

Wednesday 12 August 2009

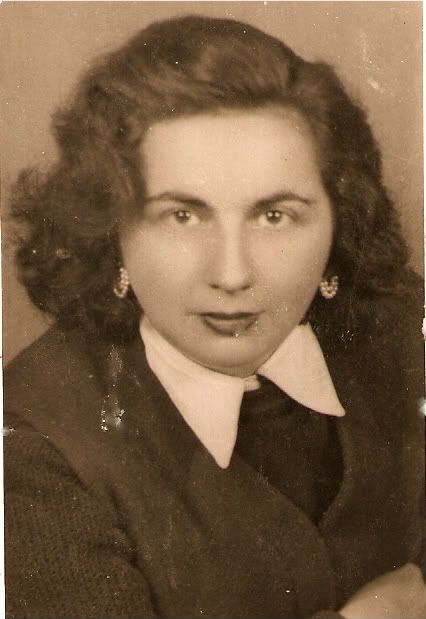

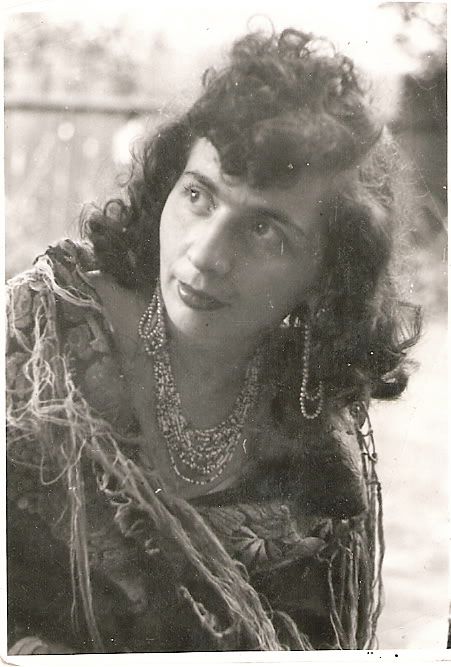

Domain: Three pictures of my mother

I was just trying to learn the code for aligning pictures with space between and now I have it. The girlhood picture on the right has been up before but the two on the left I received from my father on Sunday. I can't date them exactly but the one in the middle might be 1954.

But now that I have them up there, a little more on her domain, about which I have written a few earlier posts.

I mean a domain restricted by ill health. She was otherwise a vigorous woman who was never going to be denied and would always stand up for herself, or indeed for anything. She was never a housewife until illness broke her towards the end of her short life of fifty-one years.

I have written a number of poems about her, and the 'Flesh' part of Reel has a whole section trying to figure her out as a presence from a child's point of view. Frankly, I don't remember the deliberate gypsy look of the middle photo very clearly, not in detail, but I have a strong sense of it even now as an aspect of her identity.

The more time that passes the more complex that identity seems to be. Emotionally, psychologically, woundedly, fiercely complex. I sometimes think she might be one of the supermodels for 'the artist's mother'.

One domain: the light box about which there is a separate poem in Reel. We are in the biggest room in the Budapest flat and she is scraping away at a black & white negative with a fragment of fine razor blade that she holds in her fingers. She is peering at the tilted surface of the light box, fully absorbed. I am sitting nearby abstractedly staring at her. I hand her my homework. My task for the day has been to decorate the lined borders of the exercise book with a folk design of tulips, alternating right-way-up with upside-down. But something is wrong. And then I say something wrong. Suddenly she is in a fury. She rises from her chair and hits out at me with a book. It doesn't hurt very much but it's a shock.

She sits down again, breathing more heavily.

I have no memory of her as in the picture on the left. That was a bygone secret self drawn from the well of Elsewhere. The nature of that Elsewhere is probably the best key available to the identity I am now reaching for.

Mandelson Pussycat

The radio is on and Peter Pussycat Mandelson is being interviewed by Evan Davis. I find my entire metabolism goes into shudder mode. My organs freeze up. What a repulsive, reptilean, slime the man is!

I know this is short. I know I am not arguing the case. I am just registering this in the way a thermometer registers a dip in the temperature of the room. The method is to talk over every question, patronise the interviewer (and so the listener too), talk only about what you want to talk about (which is only about the other side, nothing about your side), refuse to answer any questions, and then - having occupied 95% of the time - complain about not being able to get a word in edgeways. He is a cross between a sarcastic schoolteacher, a gangland boss and the traditional snake-oil salesman.

He is asked about the effect of the current recession on the poor. Just remind me of the place from which he has just returned on holiday?

Oh yes, Corfu with Nat Rothschild.

If anyone in the world could persuade me to vote Tory it would be Mandelson.

*Just a little further reminder of Mandelson, Rothschild, Osborne from The Guardian of 22 October last year.

Osborne, who was backed last night by his leader, David Cameron, was forced to admit he had been involved in a conversation at the villa of financier Nat Rothschild about the way a donation could be secured from Deripaska.

On a day of extreme political danger for Osborne, Rothschild, a regular fundraiser for the Conservatives, revealed he was willing to go to court to prove his claim that Osborne had not only wanted to secure a donation from the Russian, but had been party to discussions as to how this could be made legal.

Bold type courtesy of myself.

*

While on politics I picked this up from Norm, via Freemania. It's a How British Are You test. The questions, so it says, are from the actual British citizenship test. I failed with 71% (70.8% to be precise), the pass mark being 75%. Norm? Hah! A mere 58% Clearly a foreigner, not up to Hungaro-British standard!

On the other hand 86% of actual Brits fail. But seeing as they're Brits the failure will have been valiant.

I would be curious to know how people reading this have fared / might fare. Freemania has a very smug grin on his 87.5% face.

*

update

Kind J from Cambridge University Library, who is in fact my archivist - the man to whom I passed all those box-files of letters and who put them into order and, what is more, turned flittering bits of Szirtesiana into a very flattering exhibition at the library last year - writes to say he scored 100%, thereby blowing Freemania clear out of the water.

ps I now suspect J is a spy. It is Cambridge, after all. And it's too good, J. Too damn good. I think J is really Colley Cibber and I claim my £5.00!

Tuesday 11 August 2009

Face, Vanity and Presence

The Márai moves on and now, at last, it is the ex-maid's turn to speak, and speak she does, very vigorously. But more of that another time. I want to think about the face here. It springs out of the Facebook site where I have been sticking old (some very old) and some very new pictures of myself, partly out of curiosity and partly out of the joke of the site being called Facebook.

There are few things more curious than one's own face. And I do mean curious. not engaging or handsome or valuable or anything. Just curious. Just now I was writing something about it in poem form, but it is somewhat down the Ted Hughes 'Crow' line, and possibly too close. So it is not a good or proper or freestanding poem exactly, or I don't think so at any rate. This was it

A Man Without a Face

There once was a man without a face.

He could not grasp it.

He could not imagine it.

He could not see it.

He swam through the air faceless,

Like a bladed instrument,

Like a swatch of cloth,

Like stone rolling uphill,

Like a cloud seeking itself in a pond,

Like a likeness without a mirror,

Like a word,

Like a shout,

Like breath,

Like nothing on earth.

Am I nothing on earth? - he felt his tongue asking.

Am I feather, or stone, or leaf? - his eyes asked searching the horizon.

Am I all fingers and thumbs?

All arms and legs?

All bone and no dog?

All wind and no chest?

He ached in the depth of his eyes.

He hurt in the caves of his ears.

His heart dragged in him.

His liver and kidneys and pancreas

And all his unnumbered organs

Were faceless and unnumbered.

What is it to be faceless? God asked,

Since Gods are not given to imagining.

Here take my face, said God.

There’s nothing behind it.

I’ve faces enough. It is yours.

Yes, Hughes like, which is a shame. But let's forget that for now (I could feel the ghost of Hughes pulling me one way). It is about knowing nothing, or next to nothing, about one's face as an object. I am generally surprised when I see mine in a photograph, in much the same way as I am when I hear myself recorded. It is, I know, a form of self, but it's the least known, partly because it is an effect: the effect of the way it moves through the air, turns this way and that, forms a smile, a grimace, a frown or a blank. We cannot see or feel our presence as others see and feel it. We lack certainty.

But how much effort people put into 'looking their best' for photographs (mea culpa)! It is as if we wanted posterity to fancy us, or respect us, or be taken in by us. We want to project the face into a position of love and power.

When I touch my face it feels as strange as if I were handling some exotic object. It is neither nice or nasty. It's just that part of myself that is most registered by the world but which I myself can never register. When I look at myself in the mirror I am 'pulling a face'. There are things I want to see there. Grimacing won't do. I know that's just as much of a cheat. When someone catches me in an informal shot, when I am speaking say, I am vaguely horrified. There I am frozen in a stillness I am never aware of, one I don't own. I want to own myself. I am a moving object that wants to freeze certain aspects of my movement and hold it in eternity or at least some kind of odd temporal space.

Odd. Odd. Decidedly odd, all of it. It is not vanity. I do not admire my face. I don't even think well of it. But I know it's there, accompanying me everywhere.

And I see my father's ninety-two-year-old face and recall his earlier faces. As I do so a vast in-betweenness, an enormous gulf opens up and I feel myself faintly falling into it. I suppose that gulf is time. I suppose his face is the clock on which an individual time might be measured. But I can't even find the ruler, the chronometer. I can only see my own absence, widening somehow. I think I must be prepared to call that absence 'love' - love for him, this shrinking, shifting of face.

Monday 10 August 2009

Briefly: Márai on poverty

I am doing a lot of Márai posting at the moment because I am deeply immersed in translating him, that is in between others, like Krasznahorkai and various poets. I do far too much of this sort of thing and I wake in the morning, saying to myself: Stop it and write your own grands oeuvres! and I think I will, I actually will stop it, once I have cleared the decks, taking on nothing more for two or three years. [Carries on talking to himself...]

Ah, Márai on poverty. The fascination of Márai is the sheer intensity and articulacy of his intellect. He feels everything and tries to describe it the way an explorer might describe a voyage. It's what makes him a thrilling read. I don't mean that his mind is a 100% original mind. In many ways he is a man of his time, a self-confessed bourgeois-cum-citoyen, but there is all this substructure and superstructure that is perfectly heroic in scale.

Here he is talking of the self-image of grinding poverty, and, opportunely enough, of its heroism. The narrator is still the man who left his wife for the maid. The maid has been away and become sophisticated. In the years she was away he persisted with his polite marriage, but the moment she returned, as if to claim him, he left his wife and forsook all his earlier advantages. He still has money though. One day he realises that she is consciously, systematically, robbing him, stealing money from their joint account and rather than going large on spending as he imagines, depositing it in an account of her own.

There is a long meditation on secrecy in a relationship and on the differences between men and women. I might get on to that some other time. But he eventually ventures onto the territory of her secrecy: the reason why she says nothing.

It was in bed I learned it and I had been observing her for a while by then. I thought she was stowing the money away for her family. She had an extensive family, men and women, people at the back of beyond, trawling about in the depths of something very like history, at a depth I could comprehend with my mind but not in my heart since my heart lacked the courage to explore secrets that lay that deep. I thought it might have been this mysterious, subterranean confederacy of relatives that had put Judit up to robbing me. Maybe they were all in debt. Maybe they were desperate to buy land… But you want to know why she never said anything? I asked myself that question. My immediate answer was that the reason she said nothing was because she was embarrassed by her poverty, because poverty, you know, is a kind of conspiracy, a secret society, an eternal, silently taken vow. It is not only a better life that the poor want, they want self-esteem too, the knowledge that they are the victims of a grave injustice and that the world honors them for that, the way it honors heroes. And indeed they are heroes: now that I am getting old I can see that they are the only real heroes. All other forms of heroism are of the moment, or constrained, or down to vanity. But sixty years of poverty, quietly fulfilling all the obligations family and society imposes on you while remaining human, dignified, perhaps even cheerful and gracious: that is true heroism.

By bed, he means in the course of their intimate life. Passages like this about the heroism of the poor are to be understood in terms of the narrator's character and experience but Márai has the gift of making us feel that everything thought and felt in the book is part of some vast essay on human fate written by a distant figure we might call meta-Márai. We are constantly invited to argue with this figure, or rather just to listen to him, as people inevitably listen - listen for ages - in all Márai's books while the speaking character goes on a riff that last pages, a chapter, a large section of the book, or indeed the whole book.

There is in fact a listening figure here too as there are in all three parts of the book, as there was in the second part of Embers. They get their ears wonderfully bent.

As to the argument (whose argument? Márai's, meta-Márai's, the character's?) about poverty and heroism, I remember reading Julie Burchill ages and ages ago when Becks married Posh on purple thrones, when she argued that it wasn't middle-class manners and taste the poor wanted but wealth. Yes, says Márai but they want recognition too. They want to be valued by others. They want credit points, Green Shield stamps of virtue. Bankable with God. With man. With Argos. And who wouldn't? I would. And they deserve it.

It is the they-ness-we-ness of this that is uncomfortable. It is as when I first encountered the grindingly poor of India. Having left them behind there remained, and remains, a sense of: We have no right. No right to speak. Not of dignity or heroism or any other damn thing, because the thing is not to speak or contemplate or praise but to get rid of the damn thing on their backs.

But that is a hard commandment, a lifetime's revolutionary commandment, and so we return to the text, a text that makes no immediate demands, simply accumulates like a bad debt.

Sunday 9 August 2009

Sunday night is... Britten Sea Interlude 1: Dawn

I have long meant to put this up, but today Joan Bakewell chose it - not this recording (Leonard Bernstein) - on Desert Island Discs, and it reminded me. We saw Peter Grimes with Jon Vickers in the role a good few years ago. Quite overwhelming. And this is as good a sense of the North Sea coast in orchestral terms as I know.

*

Down to my father's birthday. We eat, eight of us, in a Cafe Rouge which he has booked, choose the Prix Fixes, two-course. He is determined to pay but so am I. I win this one. He looks a little smaller, a little frailer, a little greyer in the skin each year. He walks with great difficulty, so while the rest could walk down to the Rouge and back I zip him round in the car. Then we return to the house for home made birthday cake, which is delicious, and talk around the table. At 5 I say we have to go because we want to get to the wrestling at Yarmouth. But first he has to take me into his small study. The wall-mounted shelves fell off at 3am last night. That was where he kept some of my books, close on 30 of them. He wants to know what to do with them once he is gone. Hang on to it for now, Dad, I say. He looks so extraordinarily frail. This is the life-arc I tell myself. He wants to give me some photographs. They are of my mother in her youth, of himself as a baby with his mother and father and some others. They are small black and white pictures. I think I might scan some in. They are mostly in a tiny red note book which turns out to be the Hungarian Communist Party's Almanac for 1956, complete with dates to remember, an outline of the success of the first Five Year Plan (assuring to know it was a great success). C drives back half the way and I read through it, skim read it really. Inside, on the plain pages, are telephone numbers he must have scribbled down then at the very beginning of 1956. The rest, as they say, is history. I find it a moving and touching gift. I don't think he has thought about it as such, but this too is him.

This is the birthday poem. It is in simple verse in simple rhythm. It skirts everything we have always known really. In other words it skirts cliché.

A Song for Ninety-Two

I think of being ninety-two,

But find it hard to get that far.

Imagination won’t quite do

To help me see myself as you.

It’s like standing on a star

Trying to guess just where you are.

And I myself am sixty now,

But that was once as hard to see.

I’ve got there but I’m not sure how.

Perhaps our senses won’t allow

A foretaste of what is to be,

Because we like to think we’re free.

Where have we come from? Hard to say.

We move through time as over grass,

Shifting position day by day,

Not made to take root or to stay.

We love, are loved, and then we pass

Like light or darkness through clear glass.

We like to think of glass as clear.

Transparency: the seeing through

The sheer delight of being here,

To say my darling and my dear

As if such words were always new,

And love was me and love was you.

We like such things. That’s how we are.

Without them we’d be smoke or dust

Drifting along from star to star,

The distance between us much too far.

We’re shining metal but we rust.

We like and love because we must.

Saturday 8 August 2009

Sea

At Winterton with friends. The weather wonderful, warm to hot, a slight cooling breeze, the sand soft, the beach wide, relatively few people. The sea advances in wedges, a line of surf here, a line there: low surf. Behind us the dunes full of moss and heather with tracks to run up or down. A red kite in the sky. Just in sight an out-at-sea windfarm, another windfarm a little way behind us. Part of the beach is fenced off for Little Tern nests. A little further along is where the seals laze in the winter. Dogs run in and out of the sea today. I wade in and feel it surprisingly warm.

*

Emil Nolde, The Sea III, 1913

The first time I saw the sea was at Westgate, Kent in early December 1956. We were lodged, along with other newly arrived refugees, in out-of-season boarding houses. Ours was called Penrhyn. Out of the front door, descending a wide road down to the sea. Rain lashing the front. A thick greyness. I remember it as a romantic experience, something utterly new. Stranger still for my parents who had lived many more years without ever having seen a sea. The thick grey power of it. I once asked my father what impression it made on him. He simply replied: Fantastic. Fantastic.

And so it is. It makes me think now of Auden's The Enchafèd Flood which begins with a comparison of the sea and the desert. In it he quotes Marianne Moore saying: 'It is human nature to stand in the middle of a thing; but you cannot stand in the middle of this', the 'this' being the sea. Then he considers the romantic attitude:

The distinctive new notes in the Romantic attitude are as follows.

(1) To leave the land and the city is the desire of every man of sensibility and honor.